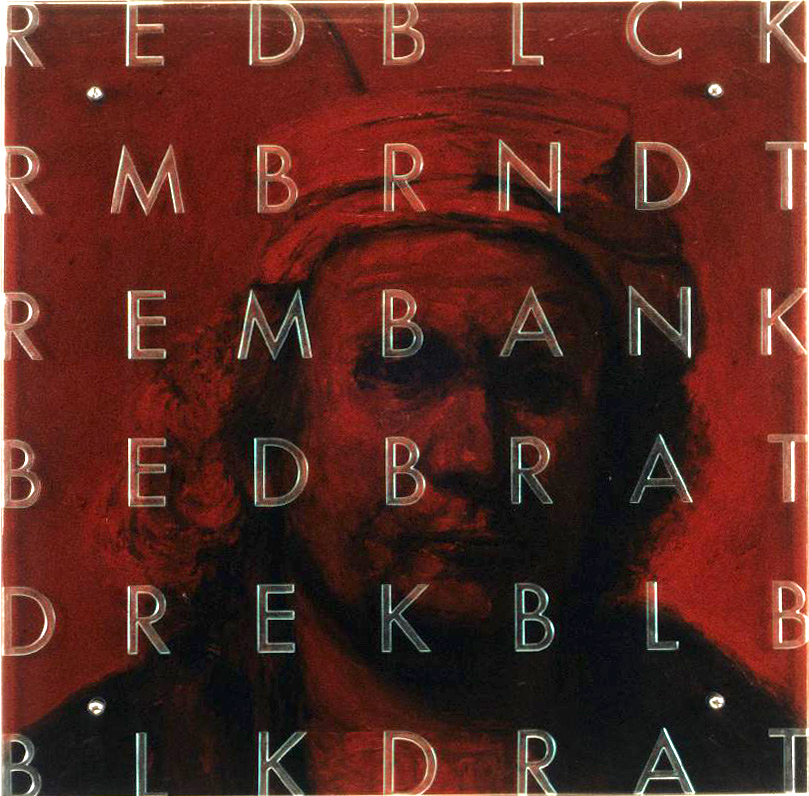

After Rembrandt, Self-portrait, 1640

TEXT:

In 1640 the artist may have changed the color of his hair.

Just one year earlier, he had moved to an enormous house on the Jodenbreestraat in the Jewish Quarter.

At the time, it was not uncommon for Jews to worry,

despite their new-found freedom.

Perhaps the change was related to anxiety about producing income sufficient to his expanding needs.

TEXT:

can well imagine the surprise of discovering, buried beneath the surface, an expression so filled with doubt and despair that we might not even be able to bear looking at it. X-rays have made it possible to know that the artist chose to conceal his personal anguish in order to

Originally there was a child, 60″ X 60″ (153cm x 153cm) Four panels, oil on wood, sandblasted glass, bolts,

After Rembrandt, Jan Pietersz. Bruyningh and Hillegont Pieters Moutmaker, 1633, Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (stolen, whereabouts unknown)

TEXT: Originally there was a child playing on the floor.

X-rays have revealed that the artist took the child out while the painting was still wet.

Recently, a thief stole the painting from a museum.

Now nobody can see it.

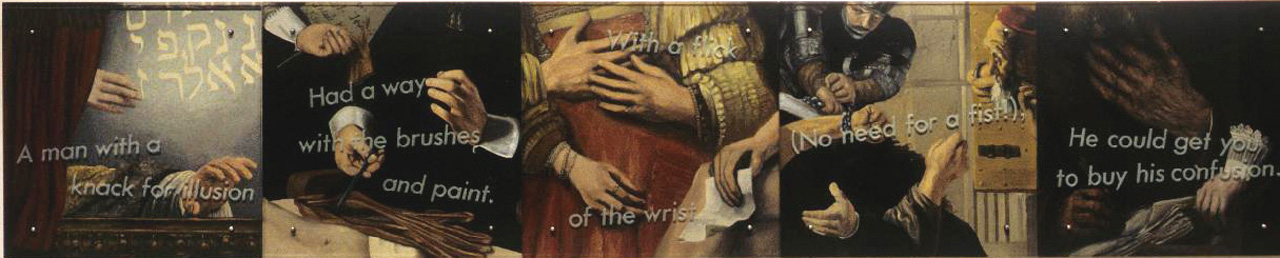

After:

Left, Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669) Woman in a Ruff Collar and White Cap

Right, Carel Fabritius (Dutch, 1622-1654) Portrait of a Man, c. 1640

TEXT:

A man with a knack for illusion

Had a way with the brushes and paint.

With a flick of the wrist (No need for a fist!),

He could get you to buy his confusion.

After all by Rembrandt (left to right)

First panel:

The holy family with painted frame and curtain, 1646

Belshazzar’s Feast, c. 1635

Second panel:

The anatomy lecture of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632

Portrait of Maerten Soolmans, 1634

Third panel:

‘The Jewish Bride,’ 1662

Bathsheba with King David’s Letter, 1654

Fourth panel:

The capture and Blinding of Samson, 1636

Samson threatening his father-in-law, c. 1635

Cornelis Claesz. Anslo and his wife Aeltje Gerritsdr. Schouten, 1641

Fifth panel:

St. Matthew and the angel, 1661

Young woman in a ruff collar, 1632

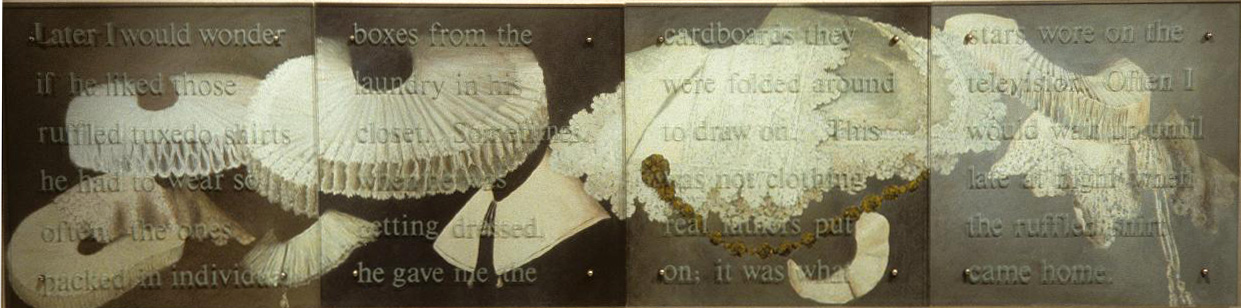

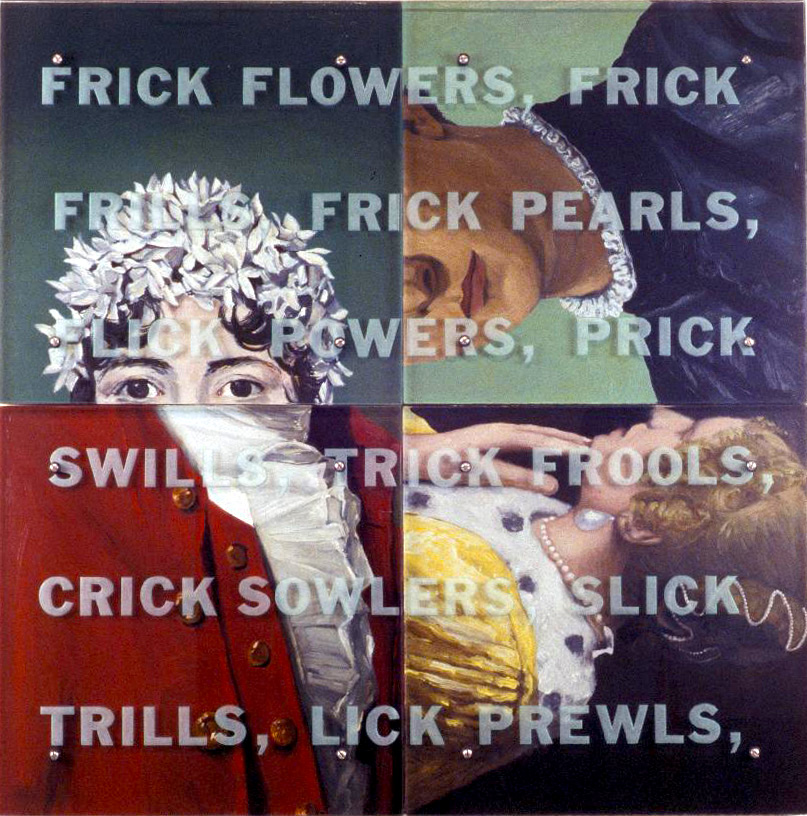

After (all from the Frick Collection, New York):

William Hogarth, Miss Mary Edwards, 1742

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, 1795-96

Agnolo Bronzino, Lodovico Capponi, 1550-1555

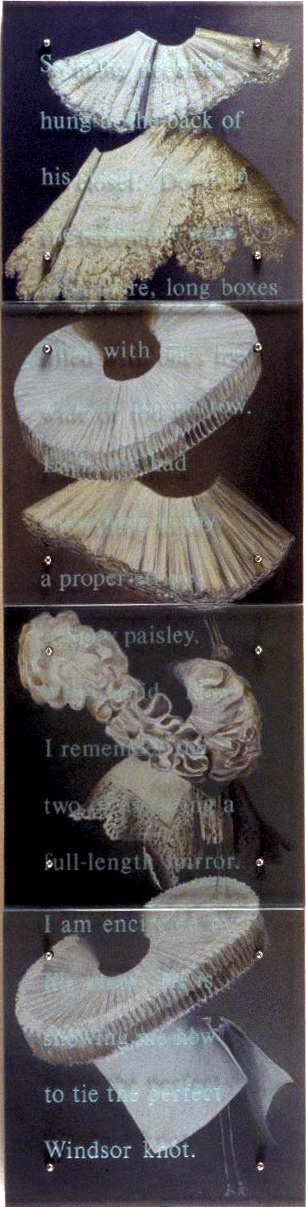

All of the collars pictured in this painting were taken from paintings by Rembrandt van Rijn.

TEXT:

Later I would wonder if he liked those ruffled tuxedo shirts he had to wear so often, the ones packed in individual boxes from the laundry in his closet. Sometimes, when he was getting dressed, he gave me the cardboards they were folded around to draw on. This was not clothing real fathers put on; it was what stars wore on the television. Often I would wait up until late at night when the ruffled shirt came home.

After Rembrandt, Jan Pietersz. Bruyningh and Hillegont Pieters Moutmaker, 1633, Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (stolen, whereabouts unknown)

TEXT:

Originally there was a child playing on the floor. X-rays have revealed that the artist took the child out while the painting was still wet. Recently a thief stole the painting from a museum. Now nobody can see it.

After Rembrandt, Self-portrait, 1661

TEXT:

So many neckties hung in the back of his closet. Down in the basement were even more, long boxes filled with ones too wide or too narrow. Each one had something to say: a proper stripe, a loopy paisley, a dull solid. Now I remember the two of us facing a full-length mirror. I am encircled by his arms. He is teaching me how to tie the perfect Windsor knot. All of the collars pictured in this painting were taken from paintings by Rembrandt van Rijn.

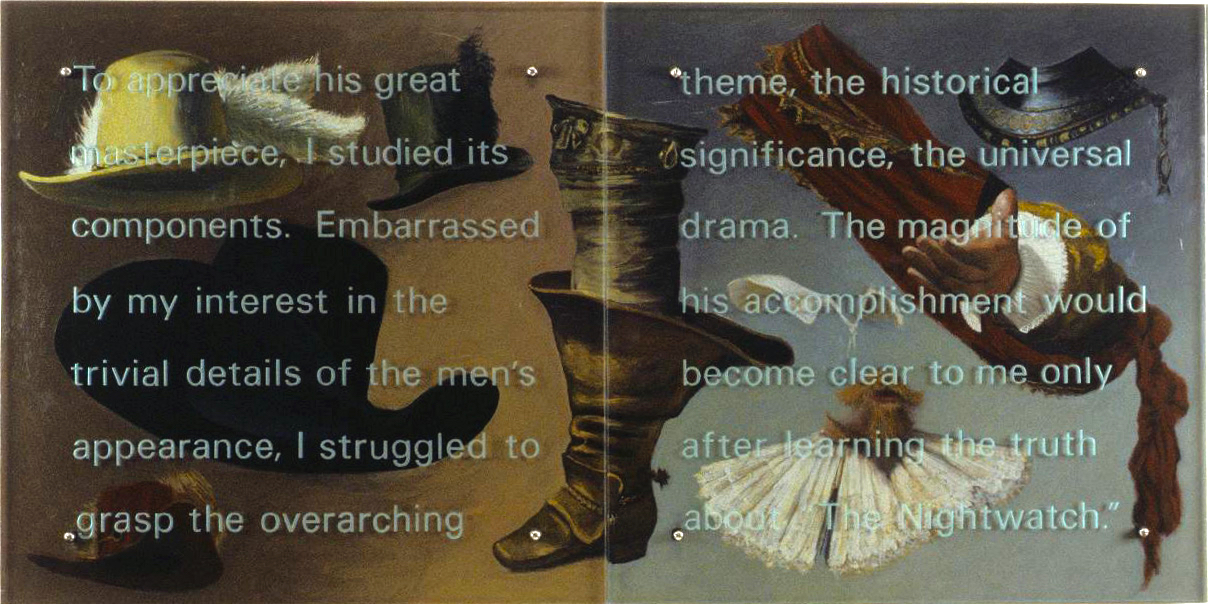

After Rembrandt van Rijn, The company of Frans Banning Cock preparing to march out, known as the Nightwatch, 1642

TEXT:

To appreciate his great masterpiece, I studied its components. Embarrassed by my interest in the trivial details of the men’s appearance, I struggled to grasp the overarching theme, the historical significance, the universal drama. The magnitude of his accomplishment would become clear to me only after learning the truth about “The Nightwatch.”

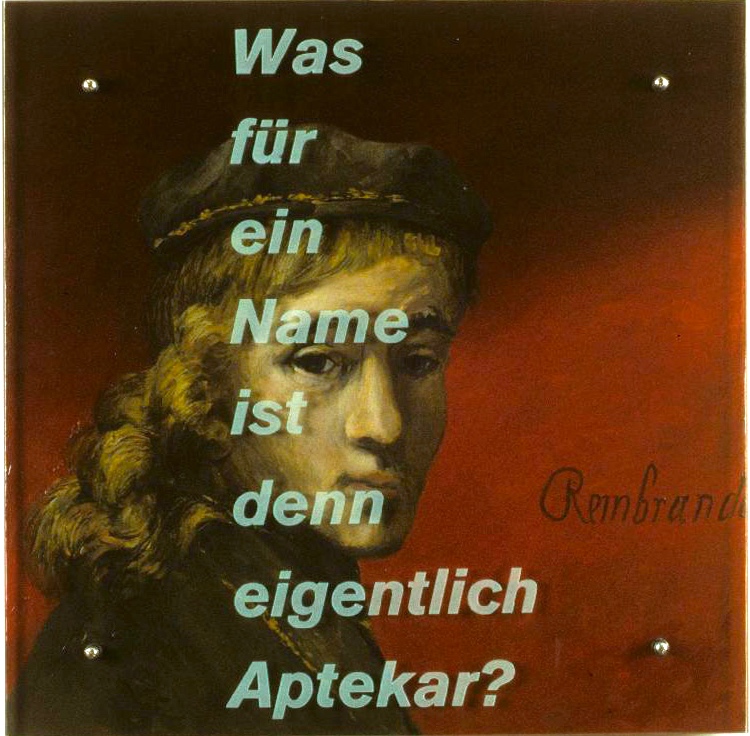

After Rembrandt van Rijn, Titus, c. 1660

TEXT (Tr. from German):

So what kind of name is that, Aptekar?

The portrait in this painting depicts Rembrandt’s son, Titus.

After Rembrandt van Rijn, Polish Rider, c. 1657

NOTE: (from wall label for 1995 Palmer Museum solo exhibition, Rembrandt Redux, written by curator, Dr. Kahren Arbitman):

Rembrandt’s Polish Rider was the prototype for this painting. The common title for Rembrandt’s painting, while long standing, is at best a compromise, because an unassailable identification for this horseman has been elusive. Rembrandt’s romantic warrior, dressed in exotic costume and armed to the teeth has engendered literally hundreds of pages of attempted explanation. Aptekar overlays this scholarly conflict with a conflict of his own.

Aptekar’s mounted warrior presents two separate, conflicting images. To the left, the confident rider sits astride his galloping steed. The impression is of masculine strength and activity. To the right, Aptekar presents the rider’s face as soft, lovely, and even androgynous. This half of the painting is quiet and contemplative. Aptekar asks questions. What if the Polish Rider wasn’t aggressive? What if he didn’t lead armies into battle? Would that make him less of a man?

Aptekar’s irony continues at another level. The “he” referred to in the painting’s inscription could just as well be Rembrandt. Much heated discussion surrounds the attribution of this painting to the master. While Rembrandt scholars have “agreed to disagree” on Rembrandt’s authorship of this famous painting, how would the public react to the Polish Rider if “he didn’t” paint this masterpiece?

After Rembrandt, Portrait of Hendrijke Stoeffels, c.1655

After Rembrandt, The sampling officials of the drapers’ guild (The syndics), 1662

TEXT: What would you say to me if you didn’t have to judge me? What would I say to you if I didn’t need your money?

All images are from paintings in The Frick Collection, New York, clockwise, from upper left:

Jacques-Louis David, The Comtess Daru, 1810

Agnolo Bronzino, Lodovico Capponi, 1550-55

Johannes Vermeer, Mistress and Maid, 1665-70

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, 1795-96

NOTE: This painting pokes fun at Henry Clay Frick’s attempt to guarantee himself a favorable place in history by bequeathing his art collection to the public. While his collection remains a famous source of pleasure for anyone interested in art, the Frick name is infamous as well. This robber baron bears the ultimate responsibility for many deaths in the bloody suppression of the Homestead Strike in the late 19th century, a crushing event in the history of the American labor movement. As the text over details of Frick’s masterpieces dissolves into gibberish, several significant words appear: POWERS, PRICK, SWILLS (The Frick family, including Henry Clay himself, was gripped by alcoholism for generations; the family’s money originally came from farming sour mash for whiskey).