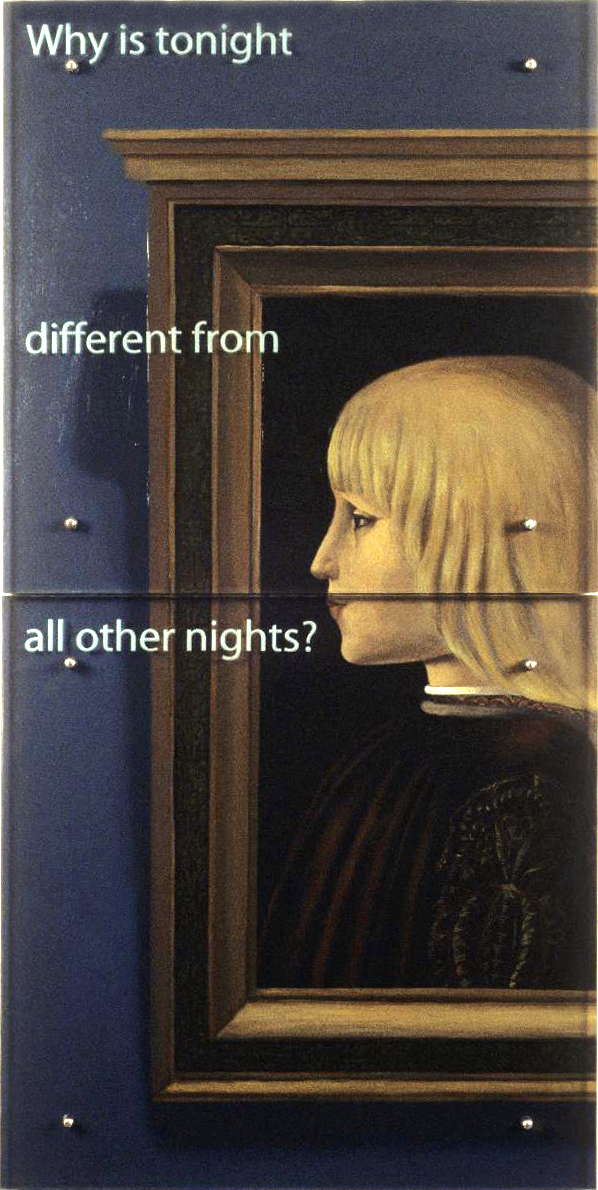

Four Questions, from Solo Exhibition, Steinbaum Krauss Gallery, NY, 1999:

TEXT IN GLASS: Why is tonight different from all other nights?

After Piero Della Francesca, Portrait of Guidobaldo Montefeltro (?), c. 1483, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

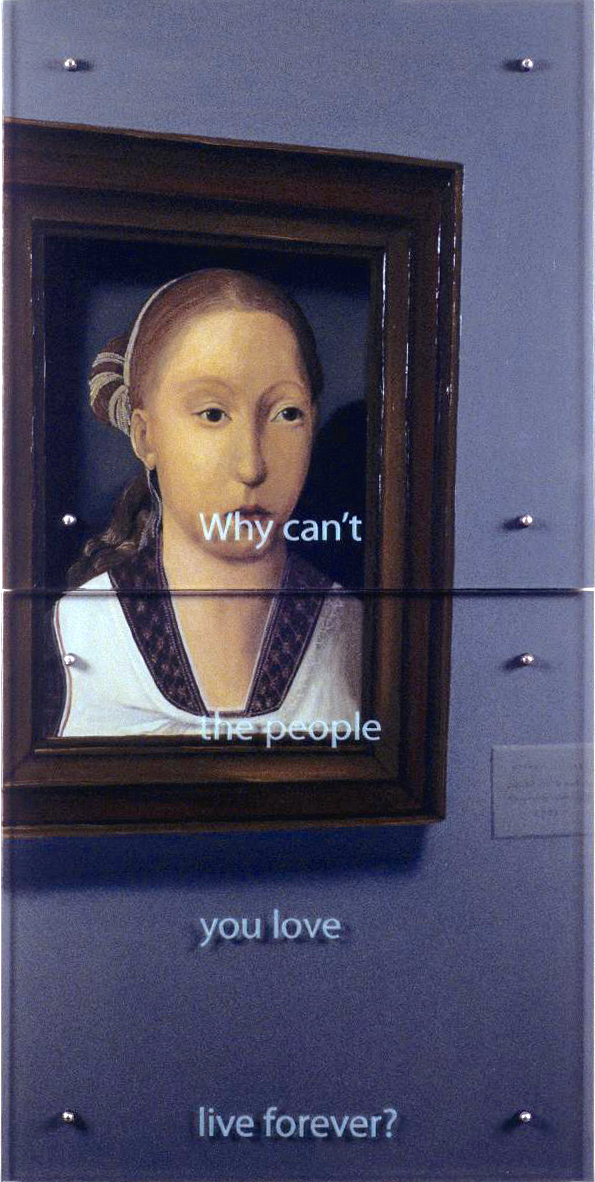

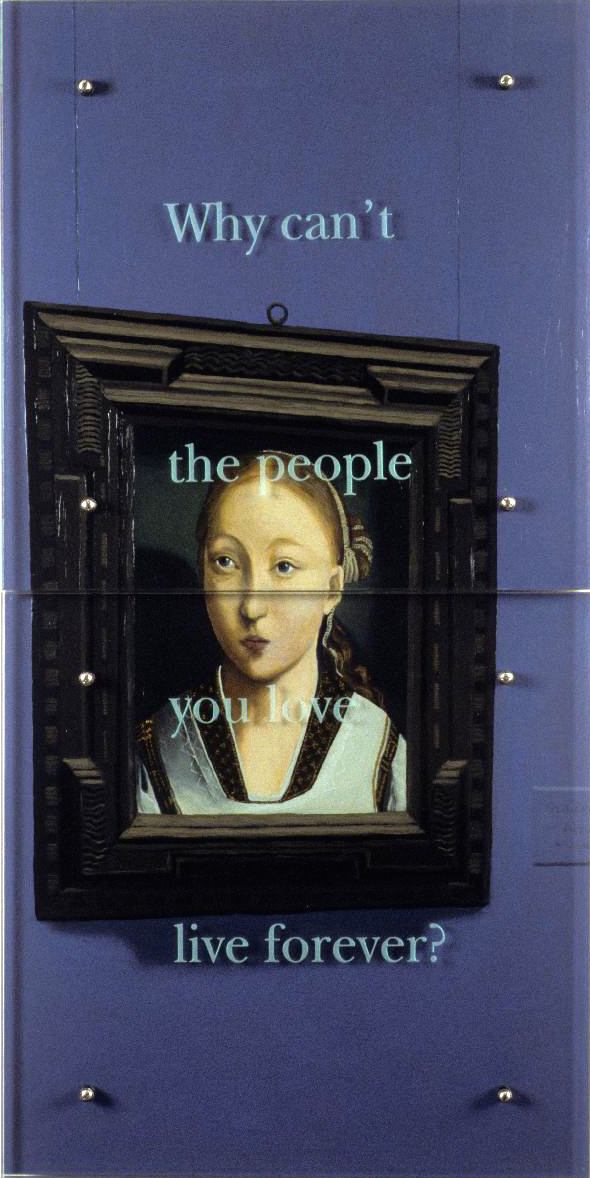

TEXT IN GLASS: Why can’t the people you love live forever?

After Juan de Flandes, Portrait of an Infanta (Catherine of Aragon?), c. 1496, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

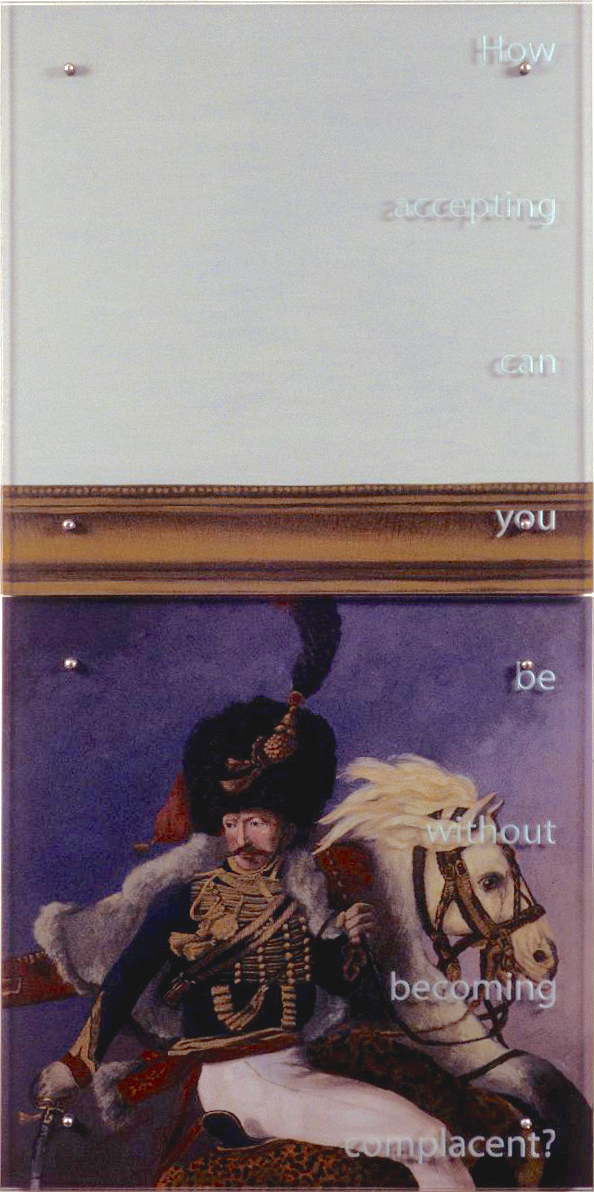

TEXT IN GLASS: How accepting can you be without becoming complacent?

After Theodore Gericault, An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards Charging, 1814, Musee du Louvre, Paris

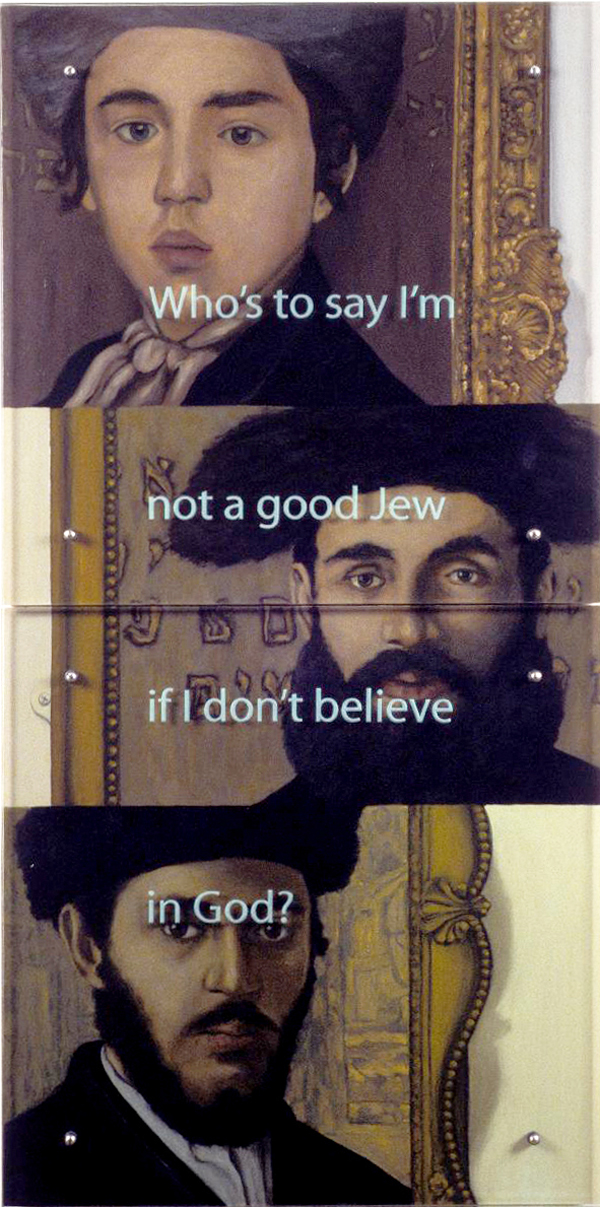

TEXT IN GLASS: Who’s to say I’m not a good Jew if I don’t believe in God?

After Isidor Kaufmann, top to bottom:

Jewish Boy, c. 1900, Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Russian “Belfer”, c. 1907/08, Collection Vera Eisenberger, Vienna

Young Rabbi from NÉ, c. 1897, Tate Gallery

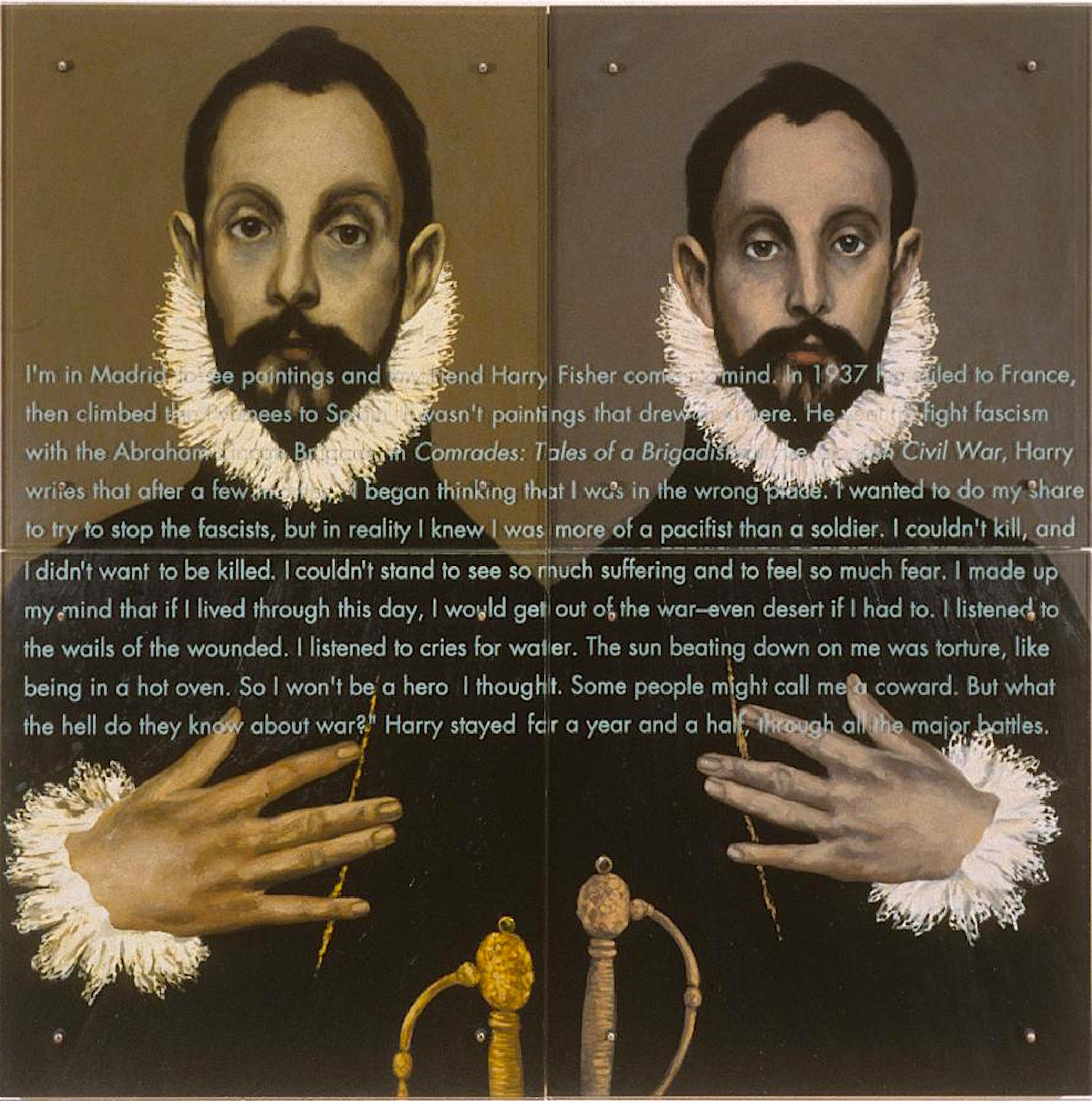

AFTER El Greco, The nobleman with his hand at his chest, c.1580 TEXT IN GLASS: I’m in Madrid to see paintings and my friend Harry Fisher comes to mind. In 1937 he sailed to France, then climbed the Pyrenees to Spain. It wasn’t paintings that drew him there. He went to fight fascism with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. In Comrades: Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War, Harry writes, that “after a few months, I began thinking that I was in the wrong place. I wanted to do my share to try to stop the fascists, but in reality I knew I was more of a pacifist than a soldier. I couldn’t kill, and I didn’t want to be killed. I couldn’t stand to see so much suffering and to feel so much fear. I made up my mind that if I lived through this day, I would get out of the war even desert if I had to. I listened to the wails of the wounded. I listened to cries for water. The sun beating down on me was torture, like being in a hot oven. So I won’t be a hero, I thought. Some people might call me a coward. But what the hell do they know about war?” Harry stayed for a year and a half, through all the major battles.

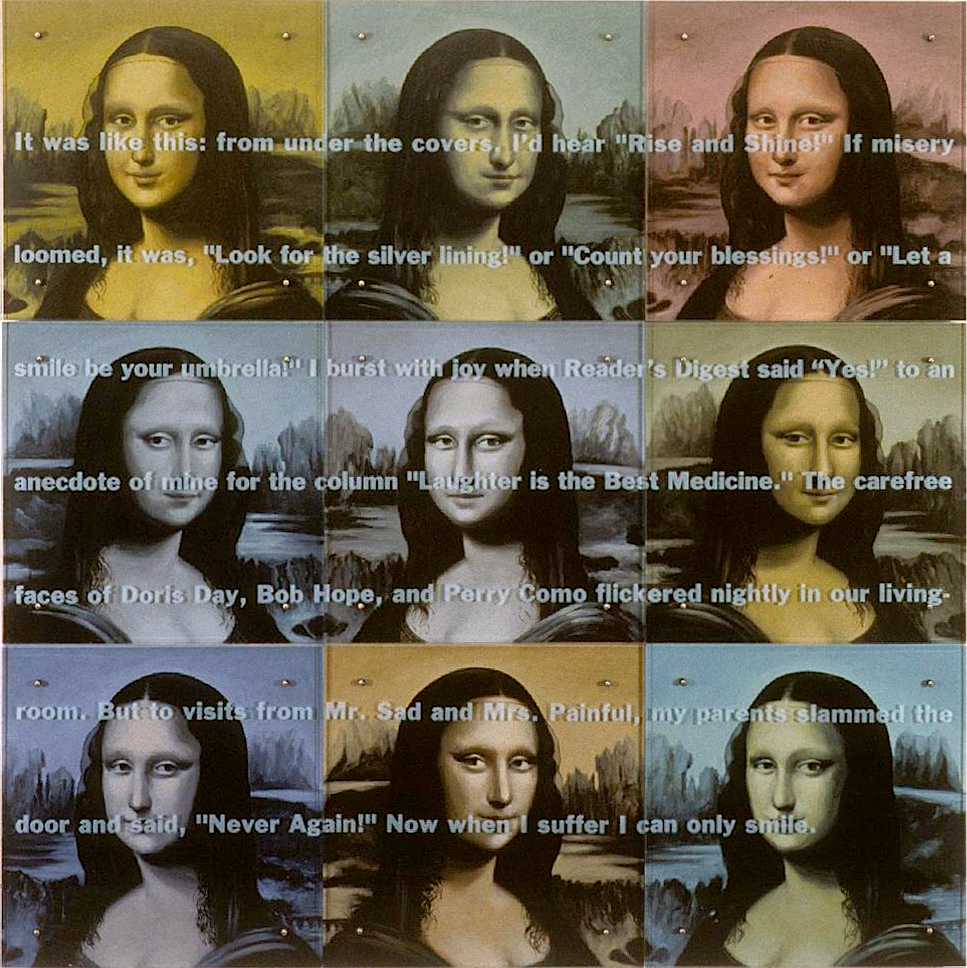

TEXT IN GLASS: It was like this: from under the covers, I’d hear “Rise and Shine!” If misery loomed, it was “Look for the silver lining!” “Count your blessings!” “Let a smile be your umbrella!” I burst with joy when Reader’s Digest said “Yes!” to an anecdote of mine for the column “Laughter is the Best Medicine.” The carefree faces of Doris Day, Bob Hope and Perry Como flickered nightly in our livingroom. But to visits from Mr. Sad and Mrs. Painful, my parents slammed the door and said, “Never Again!” Now when I suffer I can only smile.

After Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Mona Lisa, 1503-6, Musee du Louvre, Paris

Howard says to me, 60” x 60”, four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

Howard says to me, 60” x 60”, four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

TEXT IN GLASS:

Howard says to me, Henry really loves Manet’s flowers. You know, it’s his 50th this year. Couldn’t you do one just this once without the words?

After Eugene Manet, four late floral still lifes

TEXT IN GLASS:

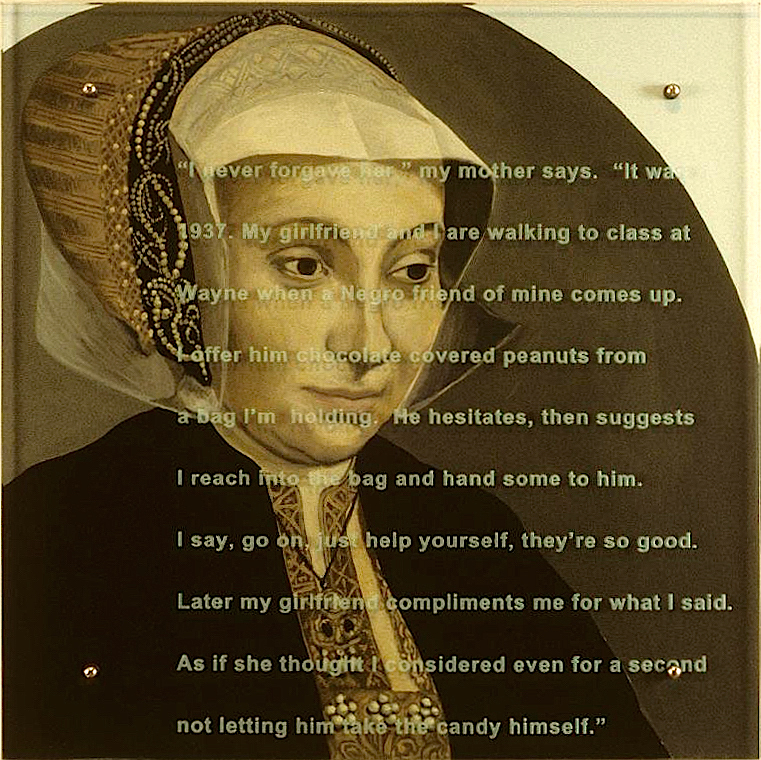

“I never forgave her,” my mother says. “It was 1937. My girlfriend and I are walking to class at Wayne when a Negro friend of mine comes up. I offer him chocolate covered peanuts from a bag I’m holding. He hesitates, then suggests I reach into the bag and hand some to him. I say, go on, just help yourself, they’re so good. Later my girlfriend compliments me for what I said. As if she thought I considered even for a second not letting him take the candy himself.”

After Barthel Bruyn the Elder, Portrait of a Woman, 1538-9, Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

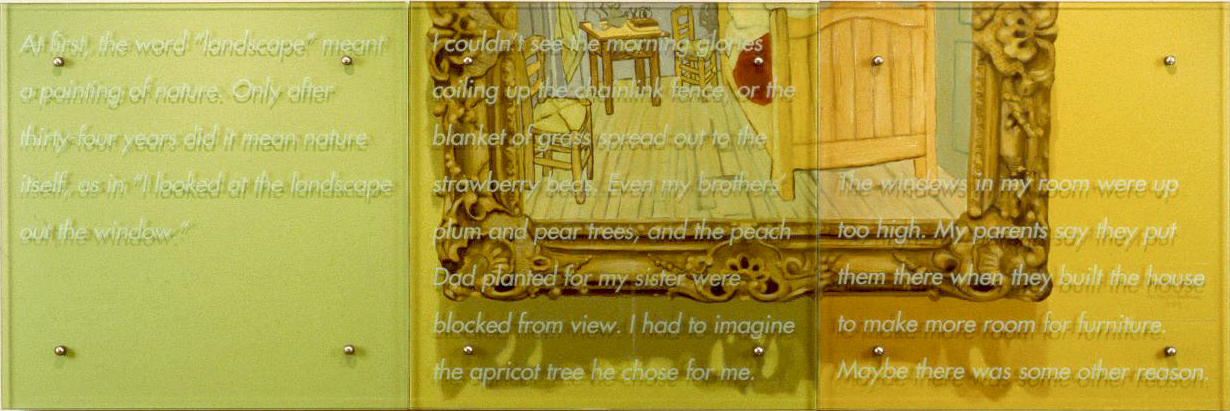

TEXT IN GLASS: At first, the word “landscape” meant a painting of nature. Only after

thirty-four years did it mean nature itself, as in “I looked at the landscape out the window.” I couldn’t see the morning glories coiling up the chainlink fence, or the blanket of grass spread out to the strawberry beds. Even my brothers’ plum and pear trees, and the peach Dad planted for my sister were blocked from view. I had to imagine the apricot tree he chose for me. The windows in my room were up too high. My parents say they put them there when they built the house to make more room for furniture. Maybe there was some other reason.

After Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh’s Bedroom, 1888, Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum

TEXT IN GLASS:

My parents say people are starving all over the world, finish your dinner. So I become a member of the clean your plate club. Nobody in India will be getting my Kosher salami on rye, no kasha knish for the Chinese.

After a detail from Four Portraits of Courtiers, Mughal, c.1615, from the Kevorkian Album, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

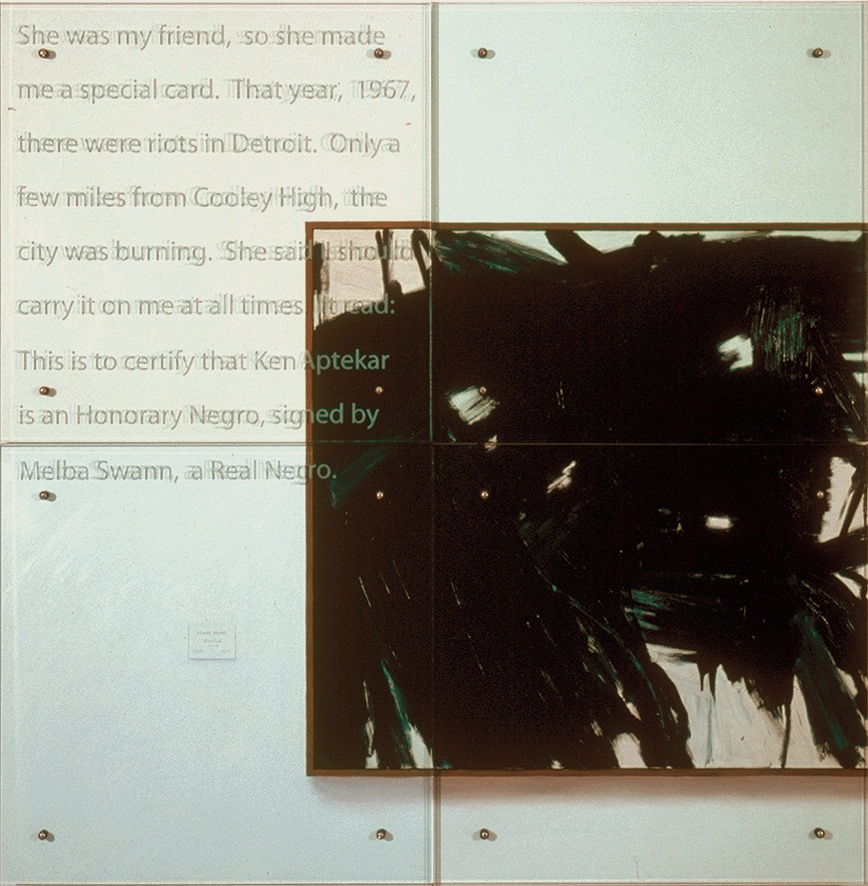

TEXT IN GLASS: She was my friend, so she made me a special card. That year, 1967, there were riots in Detroit. Only a few miles from Cooley High, the city was burning. She said I should carry it on me at all times. It read: This is to certify that Ken Aptekar is an Honorary Negro, signed by Melba Swann, a Real Negro.

After Franz Kline, Suskind, 1961, Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit

TEXT IN GLASS: To the judgmentally minded, there are either pedestals or ditches. After a discouraging day in the life of an artist, a rabbi’s daughter offers him a soothing story that her mother used to tell.

A nightingale is singing in the woods when a crow flies by. “You’re making such a terrible noise!” says the crow. “Stop singing! If you want to hear music, listen to me.” “Oh really?” the nightingale replies. “Surely you must know the nightingale is known for its exquisite song.” At that, the crow proposes a contest to decide who’s the best. A pig wanders onto the scene. Hearing their story, he offers to judge, adding how lucky they are to find such a connoisseur. The contest begins, and the nightingale sings, beautifully. Then the crow caws, loudly. Without hesitation the pig declares the crow the winner. The nightingale starts to cry. “Not only are you a bad singer,” says the pig to the nightingale, “but you’re also a bad loser!” “I’m not crying because I lost,” the nightingale replies, “but because a pig was my judge.”

After Jacques-Louis David, Consecration of the Emperor Napolean I and Coronation of the Empress Josephine in the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris on 2 December 1804, 1806-7, Musee du Louvre, Paris

TEXT IN GLASS: Why can’t the people you love live forever?

After Juan de Flandes, Portrait of an Infanta (Catherine of Aragon?), c. 1496, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum