RECENT PORTRAITS at JAMES GRAHAM GALLERY, NEW YORK

![Ken Aptekar, Portrait of the artist), 2010 60” x 60” four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts after (clockwise from upper left) Charles Demuth, Love Love Love [Homage to Gertrude Stein (?)], 1929, Fundacion Coleccion Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid Charles Demuth, Poster Portrait: O’Keeffe, 1923-24, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven Charles Demuth, I saw the figure five in gold (Poster Portrait: William Carlos Williams), 1928, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Francois Boucher, Young woman with a bouquet of roses, Private collection TEXT: NOW SHOWING K.A.!](http://kenaptekar.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Portrait_of_the_artistlo-res-1024x1024.jpg)

60” x 60” four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after (clockwise from upper left)

Charles Demuth, Love Love Love [Homage to Gertrude Stein (?)], 1929, Fundacion Coleccion Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Charles Demuth, Poster Portrait: O’Keeffe, 1923-24, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven

Charles Demuth, I saw the figure five in gold (Poster Portrait: William Carlos Williams), 1928, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Francois Boucher, Young woman with a bouquet of roses, Private collection

TEXT: NOW SHOWING K.A.!

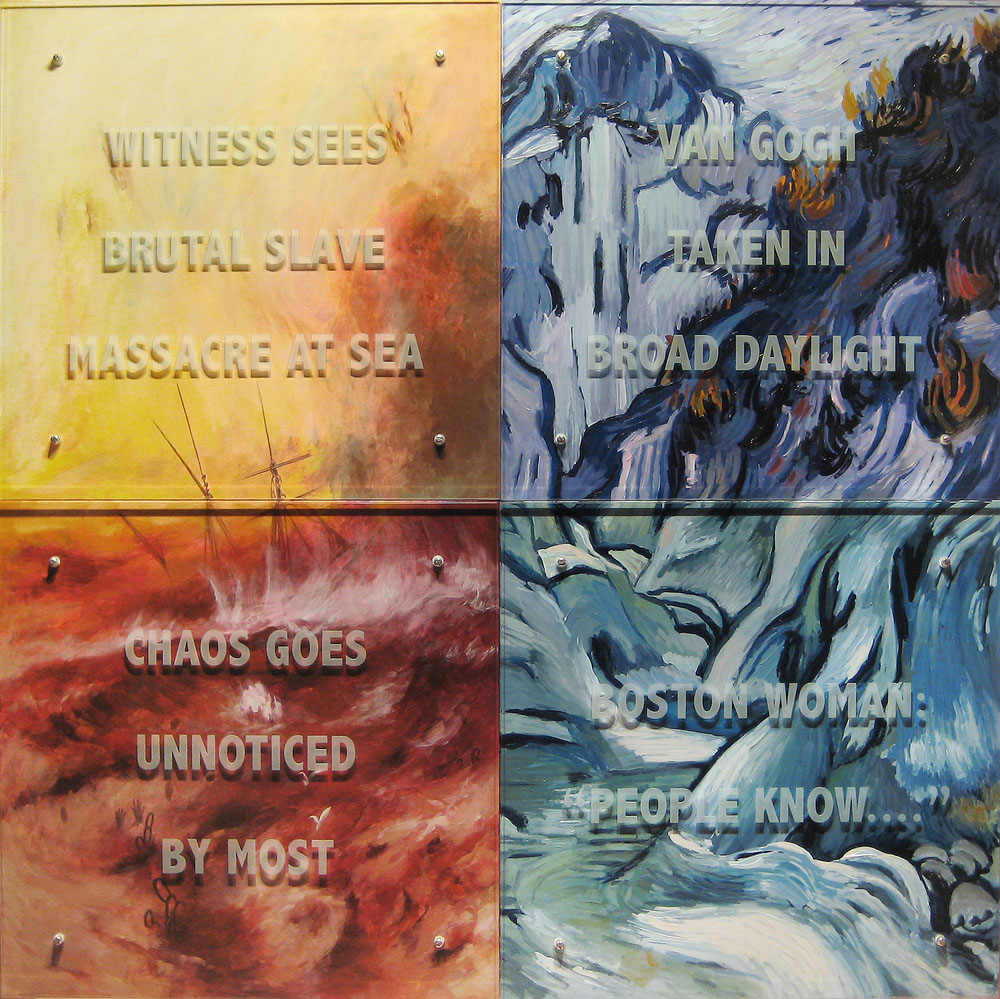

60” x 60” four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after (left) J. M. W. Turner, The Slave Ship, 1840, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

and (right) Vincent Van Gogh, The Ravine, 1889, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

TEXT: WITNESS SEES BRUTAL SLAVE MASSACRE AT SEA

VAN GOGH TAKEN IN BROAD DAYLIGHT

CHAOS GOES UNNOTICED BY MOST

BOSTON WOMAN: “PEOPLE KNOW….”

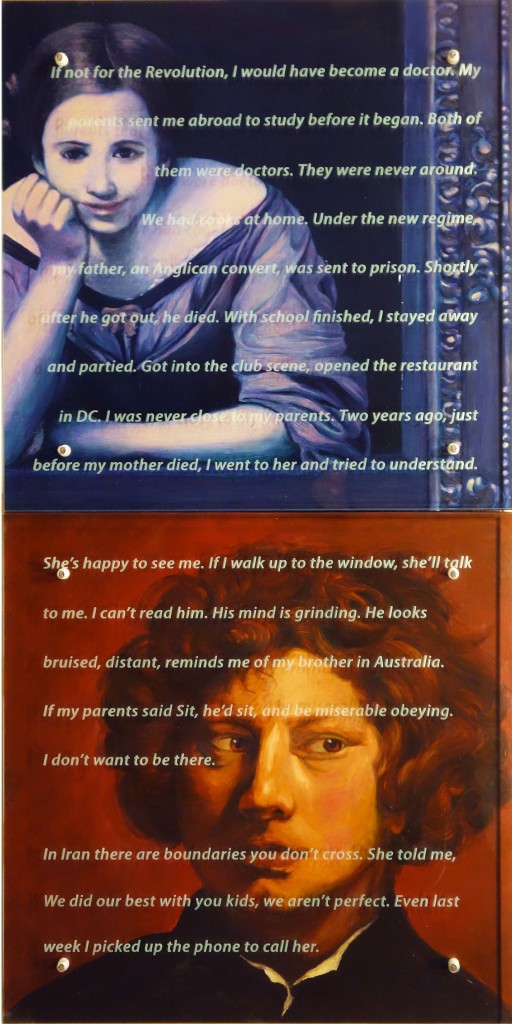

60” x 30” diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Two Women at a Window, c. 1655/1660, and

Sir Anthony van Dyck, Head of a Young Man, c. 1617/1618, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

TEXT:

If not for the Revolution, I would have become a doctor. My parents sent me abroad to study before it began. Both of them were doctors. They were never around. We had cooks at home. Under the new regime, my father, an Anglican convert, was sent to prison. Shortly after he got out, he died. With school finished, I stayed away and partied. Got into the club scene, opened the restaurant in DC. I was never close to my parents. Two years ago, just before my mother died, I went to her and tried to understand. She’s happy to see me. If I walk up to the window, she’ll talk to me. I can’t read him. His mind is grinding. He looks bruised, distant, reminds me of my brother in Australia. If my parents said Sit, he’d sit, and be miserable obeying. I don’t want to be there. In Iran there are boundaries you don’t cross. She told me, We did our best with you kids, we aren’t perfect. Even last week I picked up the phone to call her.

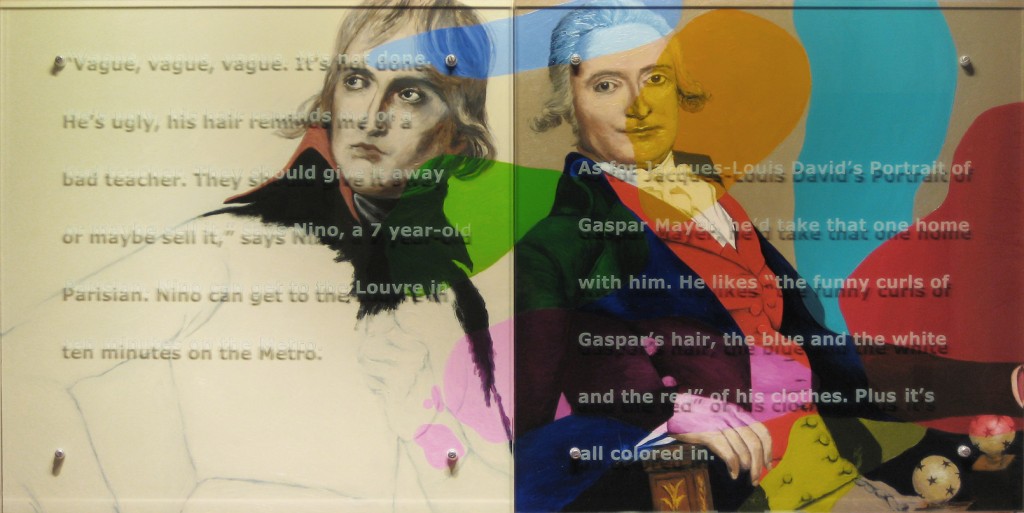

30” x 60” diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after (left) Jacques-Louis David, General Bonaparte, c. 1797-98 and Portrait of Gaspar Meyer, 1795-96, Louvre, Paris

TEXT: “Vague, vague, vague. It’s not done. He’s ugly, his hair reminds me of a bad teacher. They should give it away or maybe sell it,” says Nino, a 7 year-old Parisian. Nino can get to the Louvre in ten minutes on the Metro. As for Jacques-Louis David’s Portrait of Gaspar Mayer, he’d take that one home with him. He likes “the funny curls of Gaspar’s hair, the blue and the white and the red” of his clothes. Plus it’s all colored in.

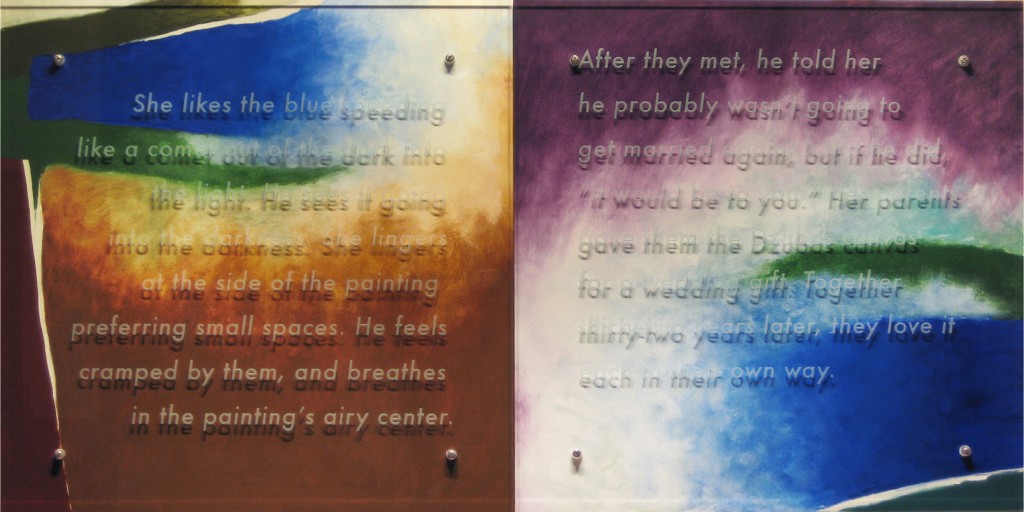

30” x 60” diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after Freidel Dzubas, Towards Darkness, 1978, Collection Peter Cummings and Julie Fisher Cummings, New York

TEXT:

She likes the blue speeding like a comet out of the dark into the light. He sees it going into the darkness. She lingers at the side of the painting, preferring small spaces. He feels cramped by them, and breathes in the painting’s airy center. After they met, he told her he probably wasn’t going to get married again, but if he did, “it would be to you.” Her parents gave them the Dzubas canvas for a wedding gift. Together thirty-two years later, they love it each in their own way.

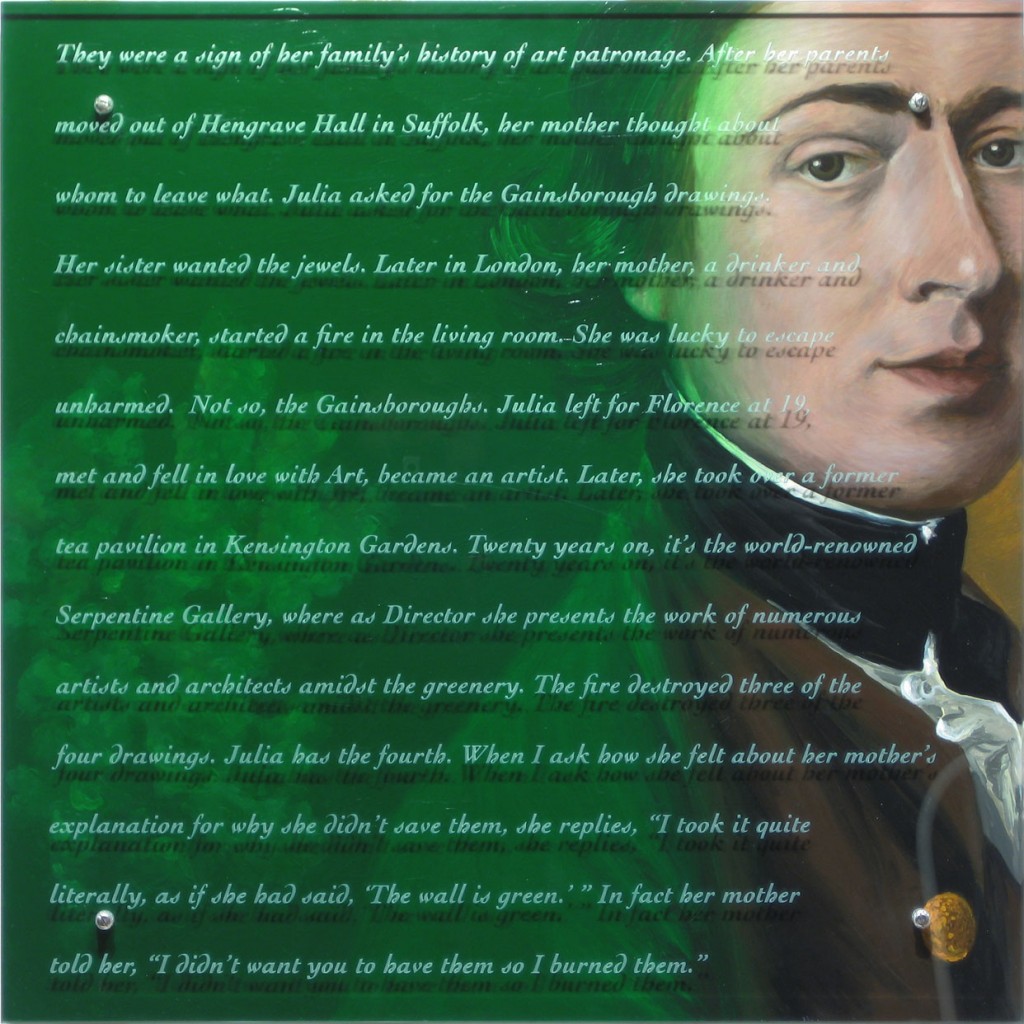

after Thomas Gainsborough, Self-portrait, 1758-59, National Portrait Gallery, London

TEXT:

They were a sign of her family’s history of art patronage. After her parents moved out of Hengrave Hall in Suffolk, her mother thought about whom to leave what. Julia asked for the Gainsborough drawings. Her sister wanted the jewels. Later in London, her mother, a drinker and chainsmoker, started a fire in the living room. She was lucky to escape unharmed. Not so, the Gainsboroughs. Julia left for Florence at 19, met and fell in love with Art, became an artist. Later, she took over a former tea pavilion in Kensington Gardens. Twenty years on, it’s the world-renowned Serpentine Gallery, where as Director she presents the work of numerous artists and architects amidst the greenery. The fire destroyed three of the four drawings. Julia has the fourth. When I ask how she felt about her mother’s explanation for why she didn’t save them, she replies, “I took it quite literally, rather as if she had said, ‘The wall is green.’” In fact her mother told her, ‘I didn’t want you to have them so I burned them.’ ”

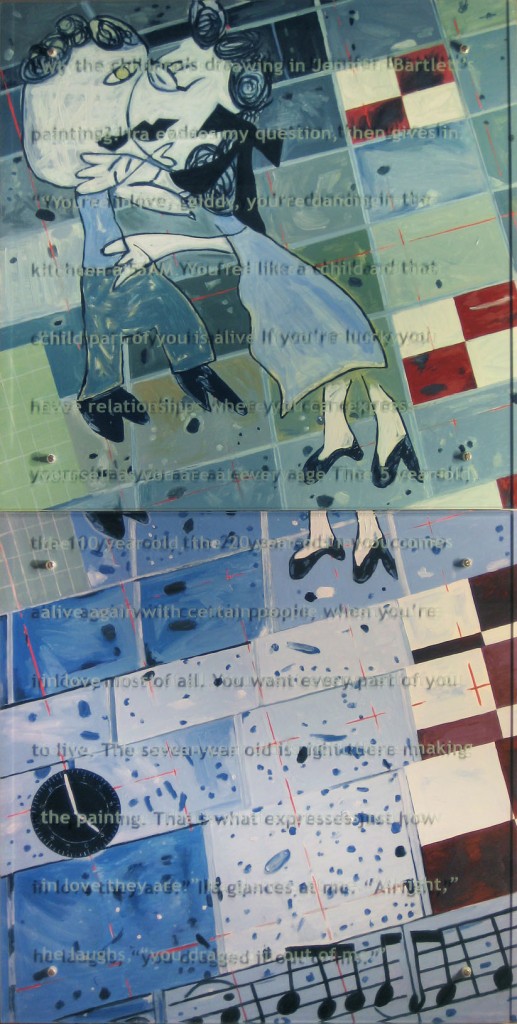

70” x 35” diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after Jennifer Bartlett, 5AM (from the series, AIR: 24 Hours), 1984, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

TEXT:

Why the children’s drawing in Jennifer Bartlett’s painting? Ira evades my question, then gives in. “You’re in love, giddy, you’re dancing in the kitchen at 5AM. You feel like a child and that child part of you is alive. If you’re lucky you have relationships where you can express yourself as you are at every age. The 5 year-old, the 10 year-old, the 20 year-old in you comes alive again with certain people, when you’re in love, most of all. You want every part of you to live. The seven year old is right there making the painting. That’s what expresses just how in love they are.” Ira glances at me. “Alright,” he laughs, “you dragged it out of me.”

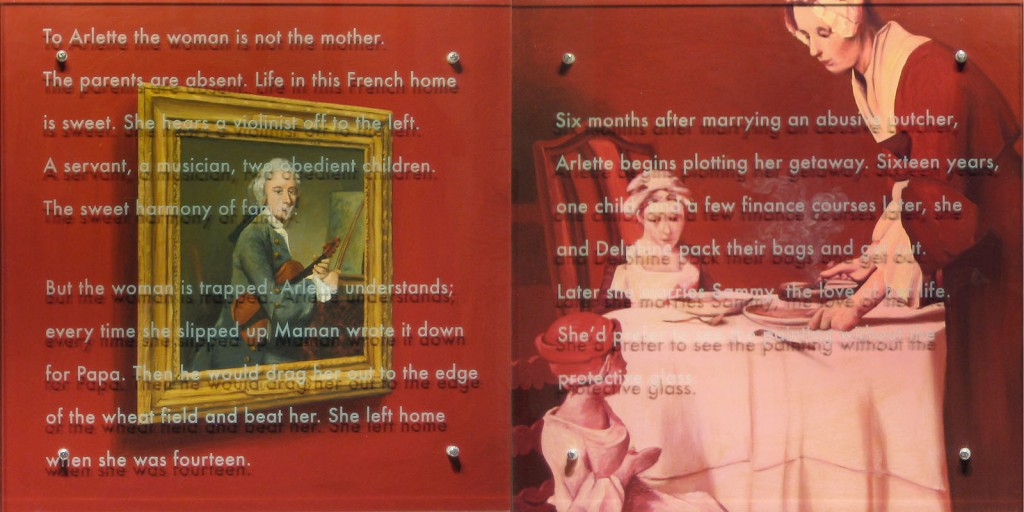

30” x 60” diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after (right) Jean-Baptiste Chardin, Saying Grace, 1740, and (left) Young Man with a Violin, or Portrait of Charles Theodose Godefroy, c.1738, Louvre, Paris

TEXT:

To Arlette the woman is not the mother. The parents are absent. Life in this French home is sweet. She hears a violinist off to the left. A servant, a musician, two obedient children. The sweet harmony of family. But the woman is trapped. Arlette understands; every time she slipped up Maman wrote it down for Papa. Then he would drag her out to the edge of the wheat field and beat her. She left home when she was fourteen. Six months after marrying an abusive butcher, Arlette begins plotting her getaway. Sixteen years, one child, and a few finance courses later, she and Delphine pack their bags and get out. Later she marries Sammy, the love of her life. She’d prefer to see the painting without the protective glass.

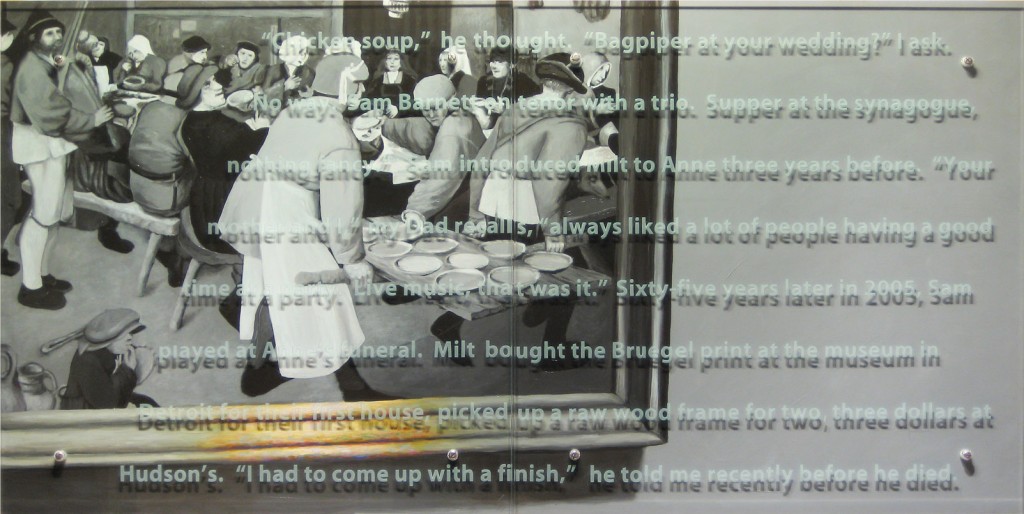

30” x 60” diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

after Peter Bruegel the Elder, The Wedding Feast, 1568, Kunsthistorisches Museum,

Vienna, TEXT:

“Chicken soup,” he thought. “Bagpiper at your wedding?” I ask. “No way. Sam Barnett on tenor with a trio. Supper at the synagogue, nothing fancy.” Sam introduced Milt to Anne three years before. “Your mother and I,” my Dad recalls, “always liked a lot of people having a good time at a party. Live music, that was it.” Sixty-five years later in 2005, Sam played at Anne’s funeral. Milt bought the Bruegel print at the museum in Detroit for their first house, picked up a raw wood frame for two, three dollars at Hudson’s. “I had to come up with a finish,” he told me recently before he died.