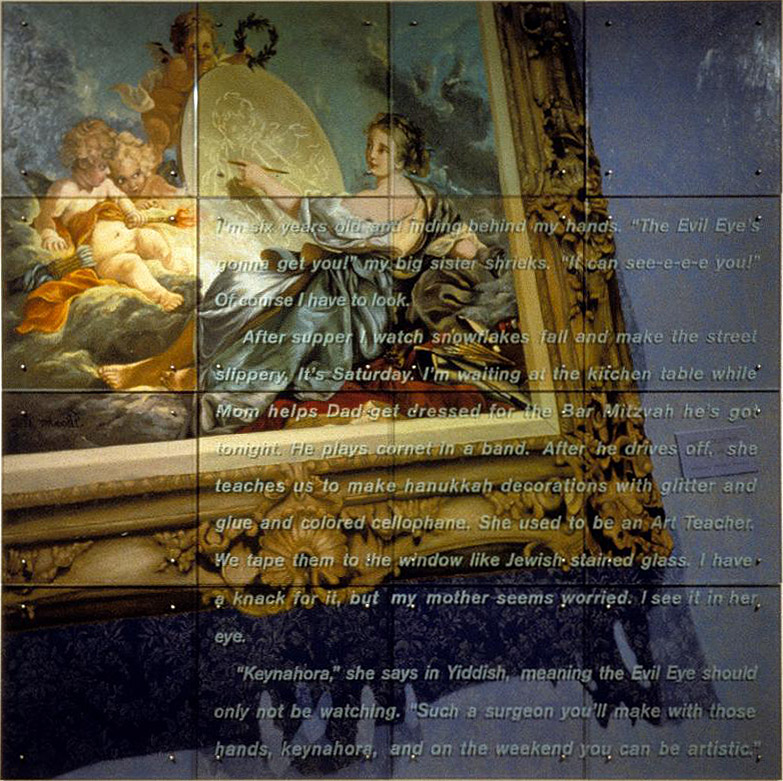

TEXT: I’m six years old and hiding behind my hands. “The Evil Eye’s gonna get you!” my big sister shrieks. “It can see-e-e-e you!” Of course I have to look. After supper I watch snowflakes fall and make the street slippery. It’s Saturday. I’m waiting at the kitchen table while Mom helps Dad get dressed for the Bar Mitzvah he’s got tonight. He plays cornet in a band. After he drives off, she teaches us to make hanukkah decorations with glitter and glue and colored cellophane. She used to be an Art Teacher. We tape them to the window like Jewish stained glass. I have a knack for it, but my mother seems worried. I see it in her eye. “Keynahora,” she says in Yiddish meaning the Evil Eye should only not be watching. “Such a surgeon you’ll make with those hands, keynahora, and on the weekend you can be artistic.”

After Francois Boucher, Allegory of Painting, 1765,

Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art

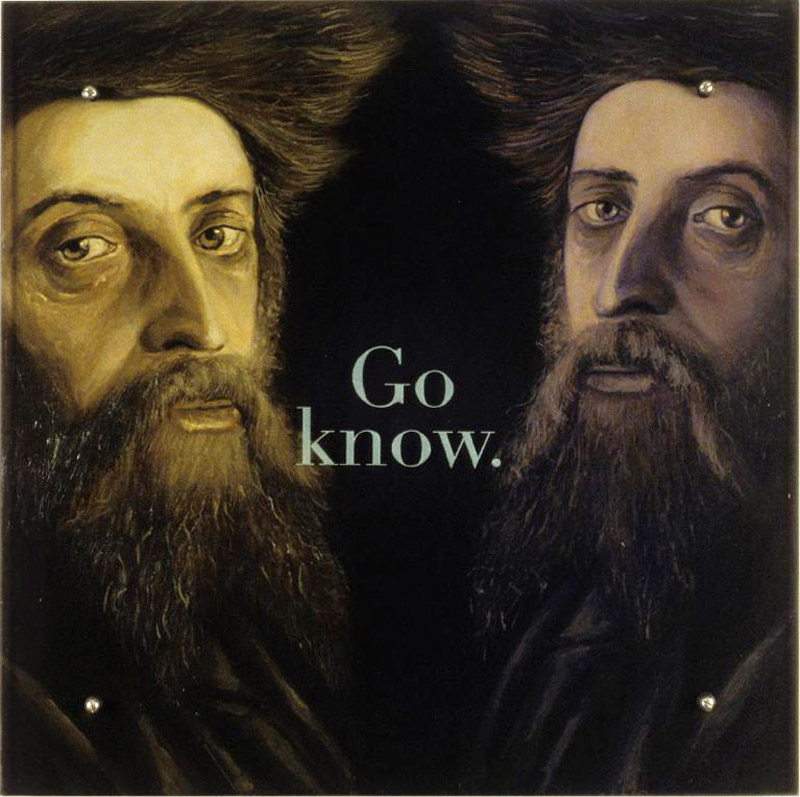

After Isadore Kauffman, Der Sohn des Wunderrabbi von Belz (Son of the miracle-working Rabbi of Belz), late 19th c.

READ ABOUT THIS PAINTING HERE TEXT: I am seven years old and they won’t let me see him. Of my two Russian grandfathers named Abraham, he was the one who didn’t change his name. Abraham Molodofsky, my mother’s father. Everything about him was thick: his hands, the hair, the accent. His lap was the safest place in the world; he’d smile and scoop me up and hold me there. One time when we stopped by his bicycle store on Vernor Highway, he said, Pick out any one you want. I never thought about what he wanted, eighteen years old and leaving his hometown of Motol forever. Recently, I learned he never got over his son quitting rabbinical school and when he had to face a small claims judge in Detroit, he collapsed from a heart attack on the floor of the courthouse. They think a seven-year-old is too young to go to a funeral. I didn’t know enough to ask.

After Isidor Kaufmann (left to right):

Portrait of a Rabbi, c.1900

Portrait of a Sephardic Jew, late 19th c.

The Son of the Miracle-Working Rabbi of Belz, c. 1897

Portrait of a Young Boy, late 19th c.

TEXT:

Abraham from Odessa changed his name. He had to if he wanted to get ahead at Ford where he got a job painting stripes on Model Ts. Fifty years later Albert retired, a vice-president in the tractor division.

Abraham from a shtetl near Minsk never changed his name. He lived in an apartment near the oldest synagogue in Detroit, ran a bicycle shop with my grandmother his whole life.

Kenneth was what my parents named me. They said it was the closest they could come to my Jewish name, “Chaim.” Hebrew for “life.” Abraham from the shtetl called me “mein Kenny.”

I was seven when I lost my Grandpa Abe. When he had to face a small claims judge, he collapsed from a heart attack on the floor of the courthouse. Grandpa Al died much later. I hate the name Kenneth.

All frames were taken from paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

TEXT:

She escaped when she was sixteen. Her father had dragged her with a sewing machine from shtetl to shtetl. She fashioned clothes for Jews, sewed them on the spot. A marriage to an older man was arranged but Mierle Pomerance knew what she wanted, and an alter kocker it wasn’t. An uncle secretly arranged passage.

Arriving in Detroit with only Yiddish and a valise she found a job in two days, two weeks later a boyfriend. And when the relatives she stayed with disapproved, Mierle, now Mary, got herself a room.

I think about Grandma drawing fashion illustrations for the paper, sneaking on the trolley to visit the Detroit Art Museum, learning to paint on her own. Picturing the view from the tallest

building in the world, she’d board a train to New York, promising in a note taped to the icebox never to forget my grandfather.

In a fabric store on Orchard Street, Mary would meet a seamstress for an uptown family with rich friends. Painting by day and sewing all night, she could just pay for the studio on Union Square and some earth colors and scraps of canvas. Nothing would have been left for frames, even if she really had gone to New York and become a painter.

After Francois Boucher, Portrait of Madame de Pompadour, 1756

TEXT:

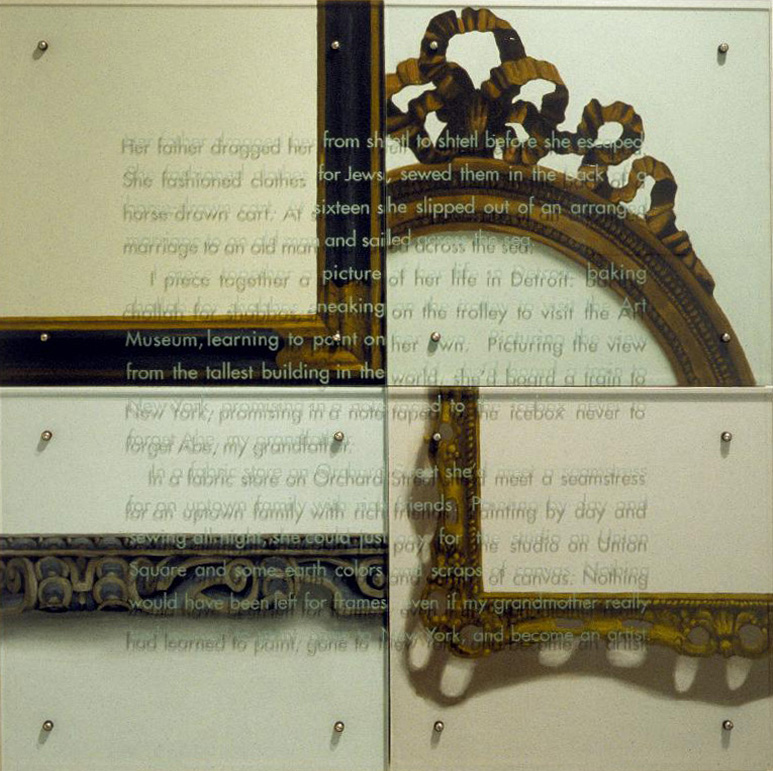

Her father dragged her from shtetl to shtetl with a sewing machine. She fashioned clothes for Jews, sewed them on the spot. A marriage to an older man was arranged but Mierle Pomerance escaped. Uncle Shmulik secretly arranged passage, and

alone she sailed to America.

Stepping off the train in Detroit, she found a job after two days. Two weeks later Mierle, now Mary, had a boyfriend; and when the relatives she stayed with disapproved, she got herself a room.

They wed in her landlord’s apartment and feasted on corned beef sandwiches. She managed the bicycle shop they ran; he shmoozed with customers. Still she made my mother’s clothes: a red and white gingham outfit, a pink suit with a blue organdy blouse. “A couturière your grandma could’ve been!” my mother says.

I escaped when I became an artist.

All frames were taken from paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

TEXT:

She escaped when she was sixteen. Her father had dragged her with a sewing machine from shtetl to shtetl. She fashioned clothes for Jews, sewed them on the spot. A marriage to an older man was arranged but Mierle Pomerance knew what she wanted, and an alter kocker it wasn’t. An uncle secretly arranged passage.

Arriving in Detroit with only Yiddish and a valise she found a job in two days, two weeks later a boyfriend. And when the relatives she stayed with disapproved, Mierle, now Mary, got herself a room.

I think about Grandma drawing fashion illustrations for the paper, sneaking on the trolley to visit the Detroit Art Museum, learning to paint on her own. Picturing the view from the tallest

building in the world, she’d board a train to New York, promising in a note taped to the icebox never to forget my grandfather.

In a fabric store on Orchard Street, Mary would meet a seamstress for an uptown family with rich friends. Painting by day and sewing all night, she could just pay for the studio on Union Square and some earth colors and scraps of canvas. Nothing would have been left for frames, even if she really had gone to New York and become a painter.

TEXT: Go know.

After Isidore Kaufmann, Portrait of Jew with Streimel, London, Private Collection

After

left, Caravaggio, The Cardsharps (I Bari), c.1594-95

right, Caravaggio, The Fortune Teller

TEXT: “Where’d you get the red hair? they’d ask. My dad said just smile and say, “Came with the head.” Nobody said, “Jews don’t have red hair, you must be somebody else’s, some Gentile’s kid.” But, why didn’t they say, “What beautiful orange hair!” Which is what it was.