Ken Aptekar: Q & A, V & A, a part of Give and Take, a joint exhibition by the Serpentine Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

For this exhibition, Ken Aptekar was commissioned to respond to the painting collection of the V&A. In the galleries of the museum previously displaying the museum’s paintings, Aptekar’s works were installed together with the source paintings he used.

READ Stuart Jeffries’ article, “Power to the People,” in The Guardian, about this project.

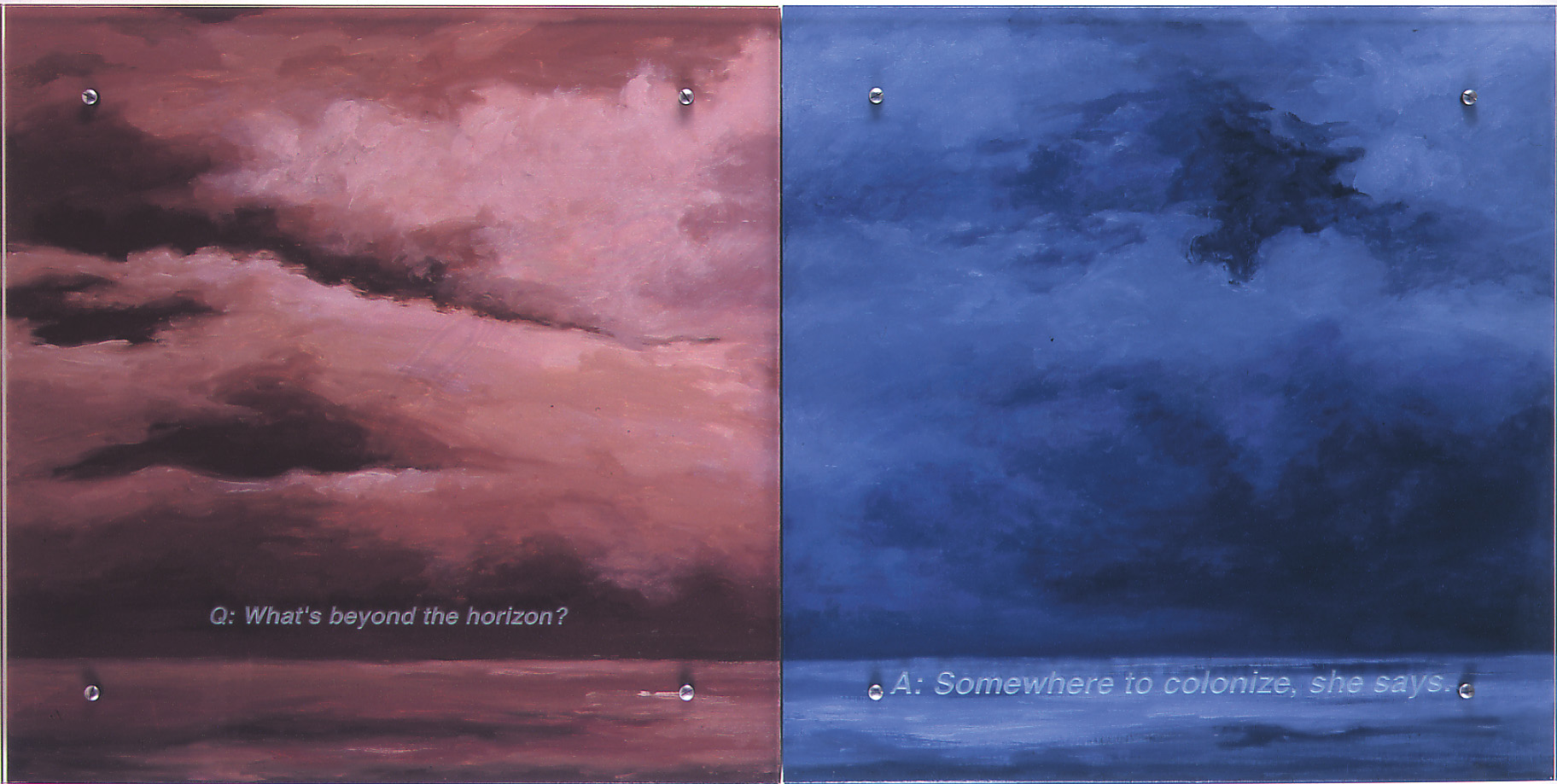

60″ x 30″ (153cm x 76.5cm),

oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

After Gustave Courbet, L’Immensite, V&A, London

TEXT: What’s beyond the horizon? A: Somewhere to colonize, she says.

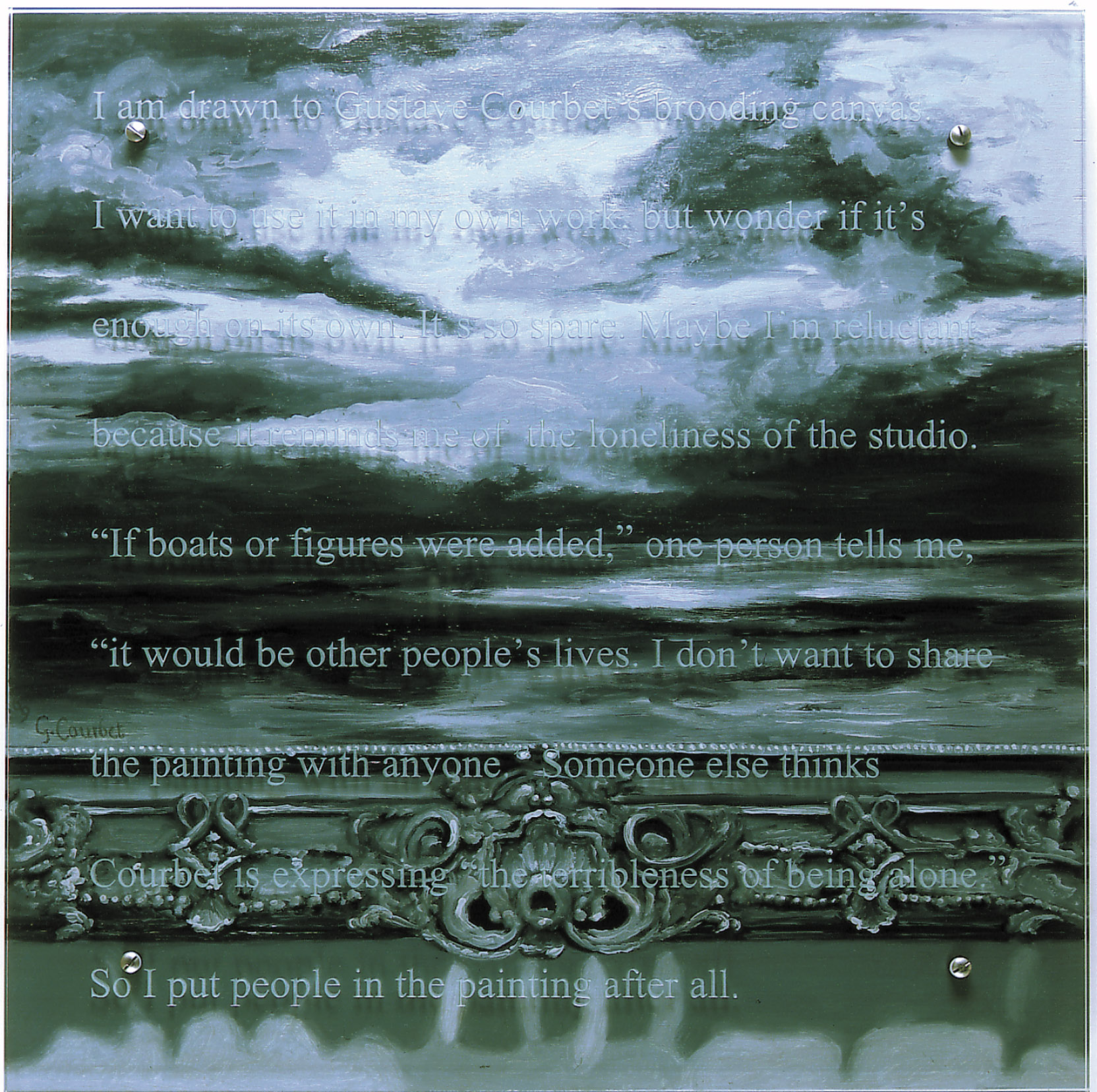

30″ x 30″ (76.5cm x 76.5cm), oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

After Gustave Courbet, L’Immensite, V&A, London

TEXT: I ask questions, it’s a Jewish thing. Here’s an example: what detail of Gustave Courbet’s seascape would you like me to cut out for you to take home? Chris answers, A little square from the center. He explains, A bit of sea, a bit of sky. I do like to go to the sea and stare out. What, I continue, is on the other side of the horizon? Who knows? Chris answers Jewish-style, a question with a question. That’s the reason I like the painting. It’s empty, a place to think about nothing. I wonder, what’s that like?

I am drawn to Courbet, 30″ x 30″ (76.5cm x 76.5cm), oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

After Gustave Courbet, L’Immensite, V&A, London

TEXT: I am drawn to Gustave Courbet’s brooding canvas. I want to use it in my

own work, but wonder if it’s enough on its own. It’s so spare. Maybe I’m reluctant

because it reminds me of the loneliness of the studio. If boats or figures were

added, one person tells me, it would be other people’s lives. I don’t want to share

the painting with anyone. Someone else thinks Courbet is expressing the terribleness

of being alone. So I put people in the painting after all.

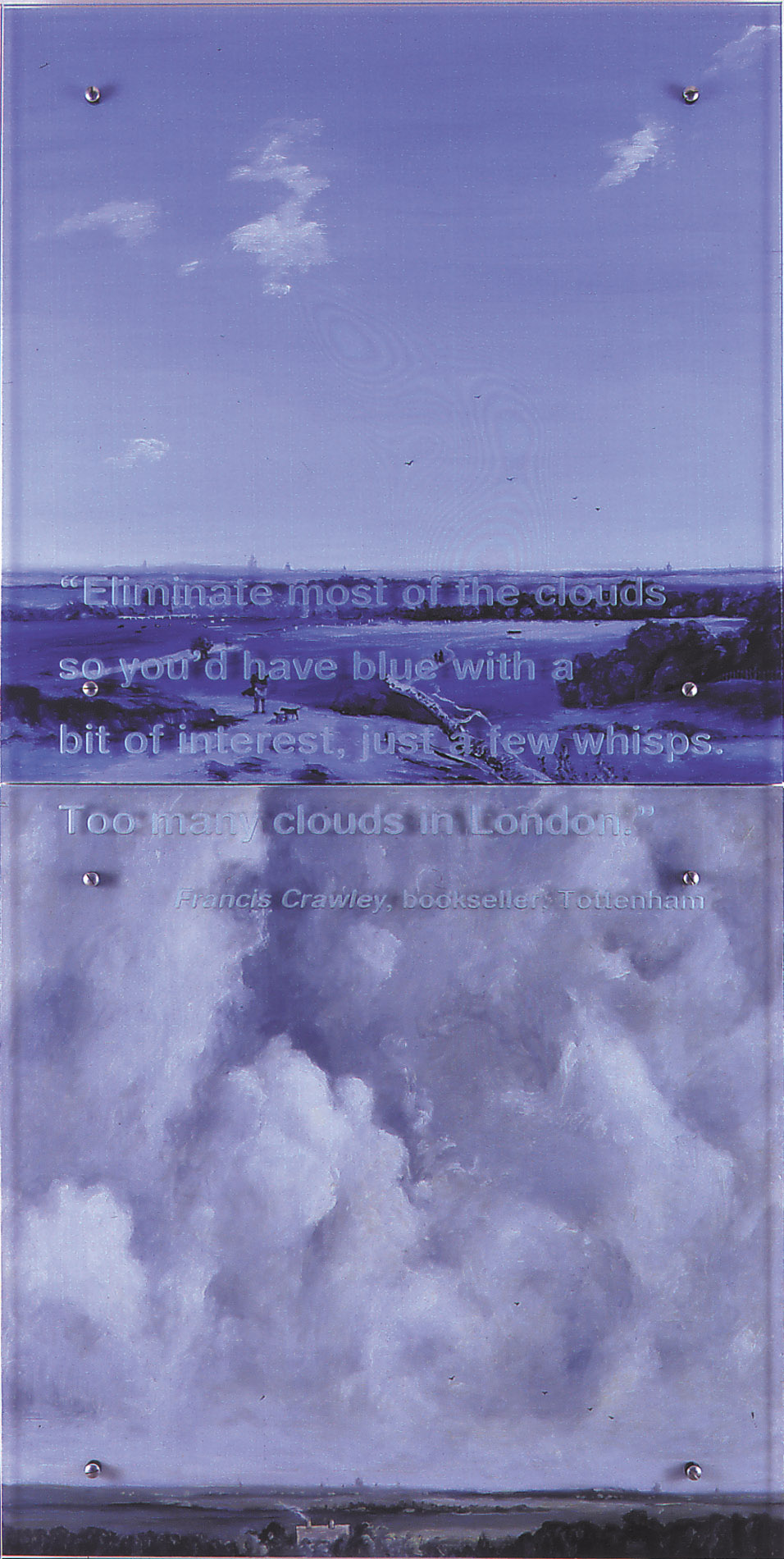

After Andreas Schelfhout, Landscape Near Haarlem, V&A, London

TEXT: Eliminate most of the clouds, just so you’d have blue with a bit of interest.

Just a few wisps. Too many clouds in London. Francis Crawley, bookseller, Tottenham

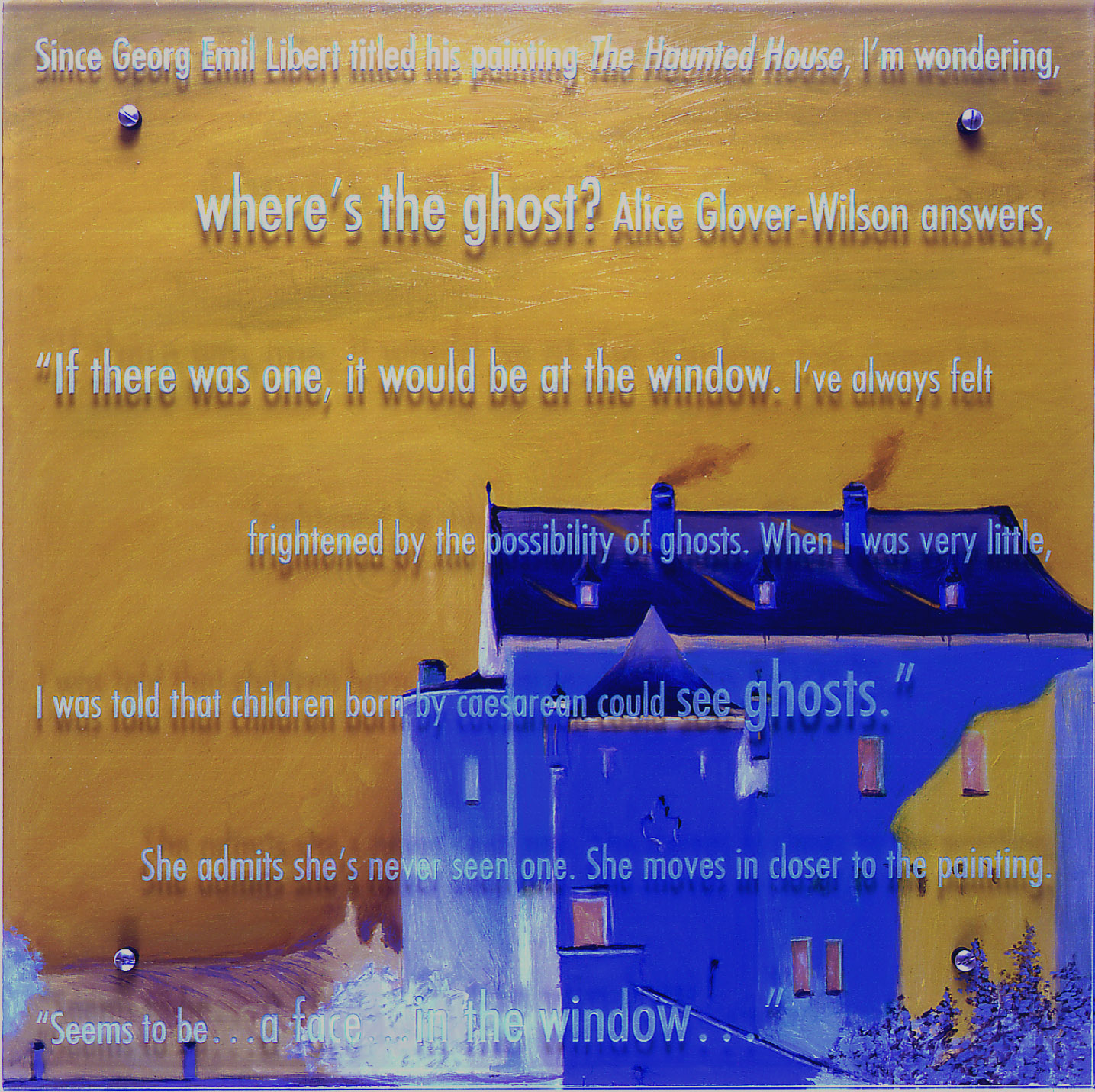

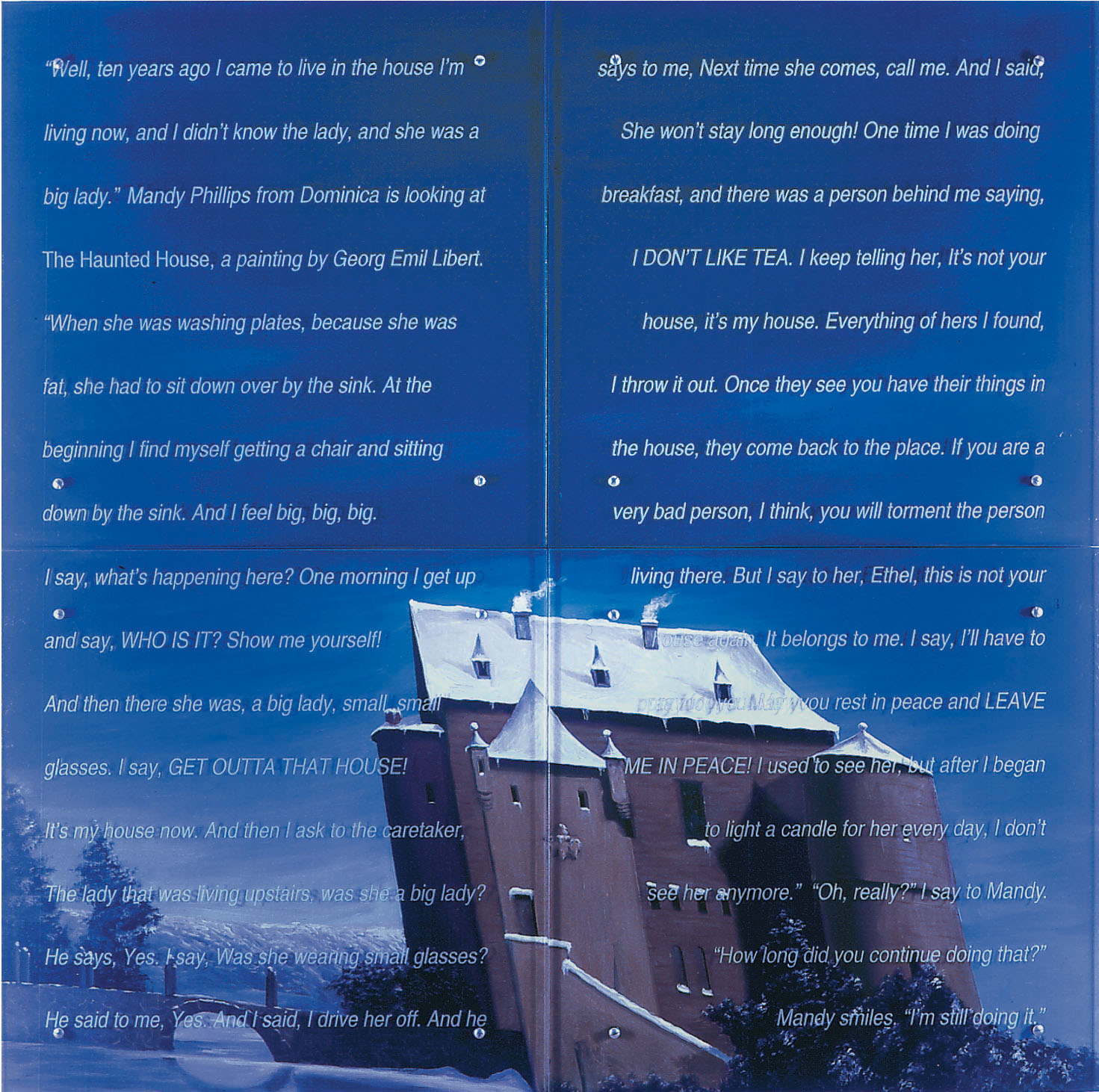

After Georg Emil Libert, The Haunted House, V&A, London

TEXT: Since Georg Emil Libert titled his painting The Haunted House, I’m wondering,

where’s the ghost? Alice Glover-Wilson answers, “If there was one, it would be at

the window. I’ve always felt frightened by the possibility of ghosts. When I was very little,

I was told that children born by caesarean could see ghosts. She admits she’s never

seen one. She moves in close to have a better look. Seems to be a face in the window….”

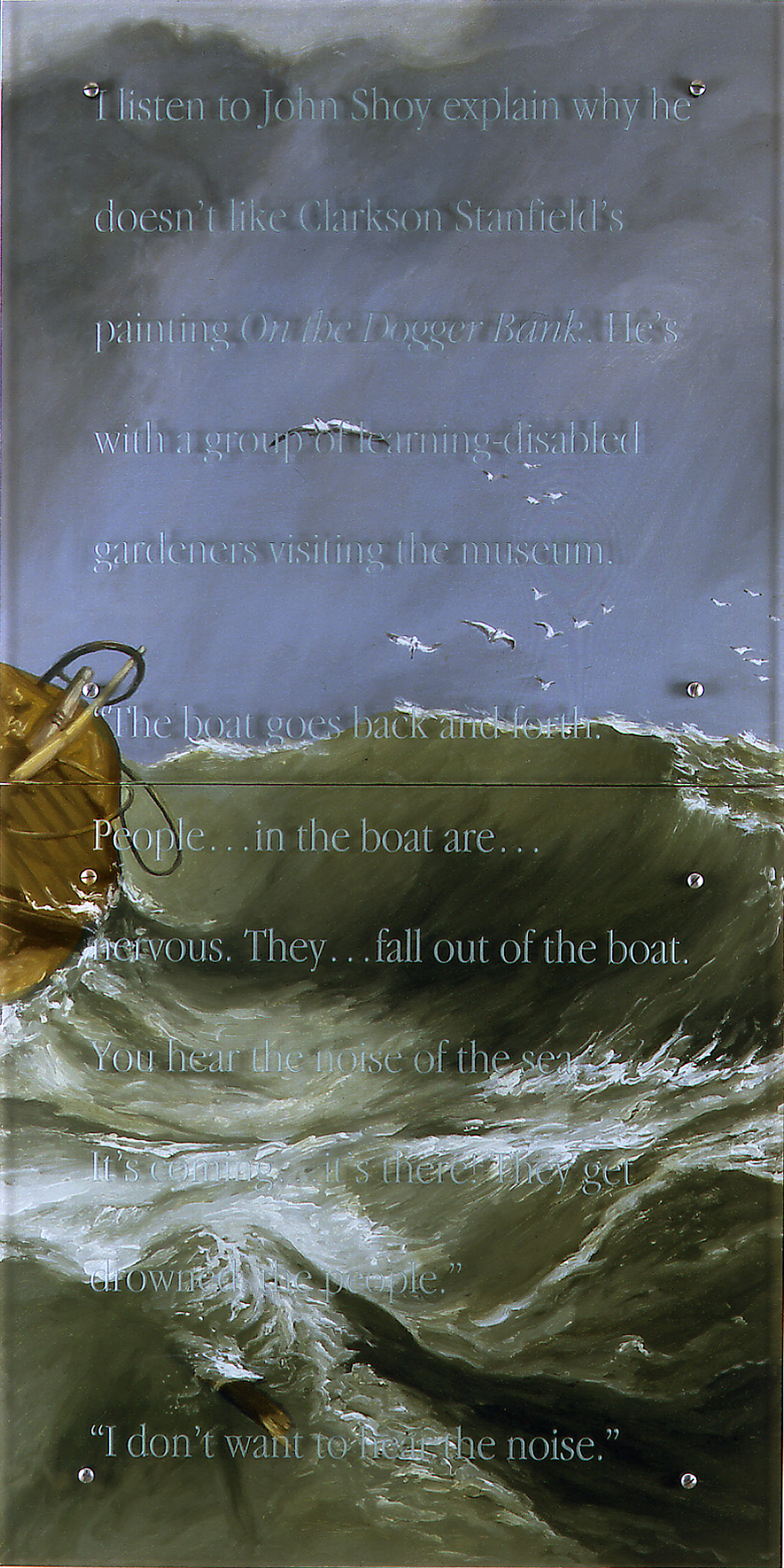

After Clarkson Stanfield, On the Dogger Bank, V&A, London

TEXT: I listen to John Shoy explain why he doesn’t like Clarkson Stanfield’s painting On the Dogger Bank. He’s with a group of learning-disabled gardeners visiting the museum. “The boat goes back and forth. People in the boat are nervous. They fall out of the boat. You hear the noise of the sea. It’s coming, it’s there! They get drowned, the people. I don’t want to hear the noise.”

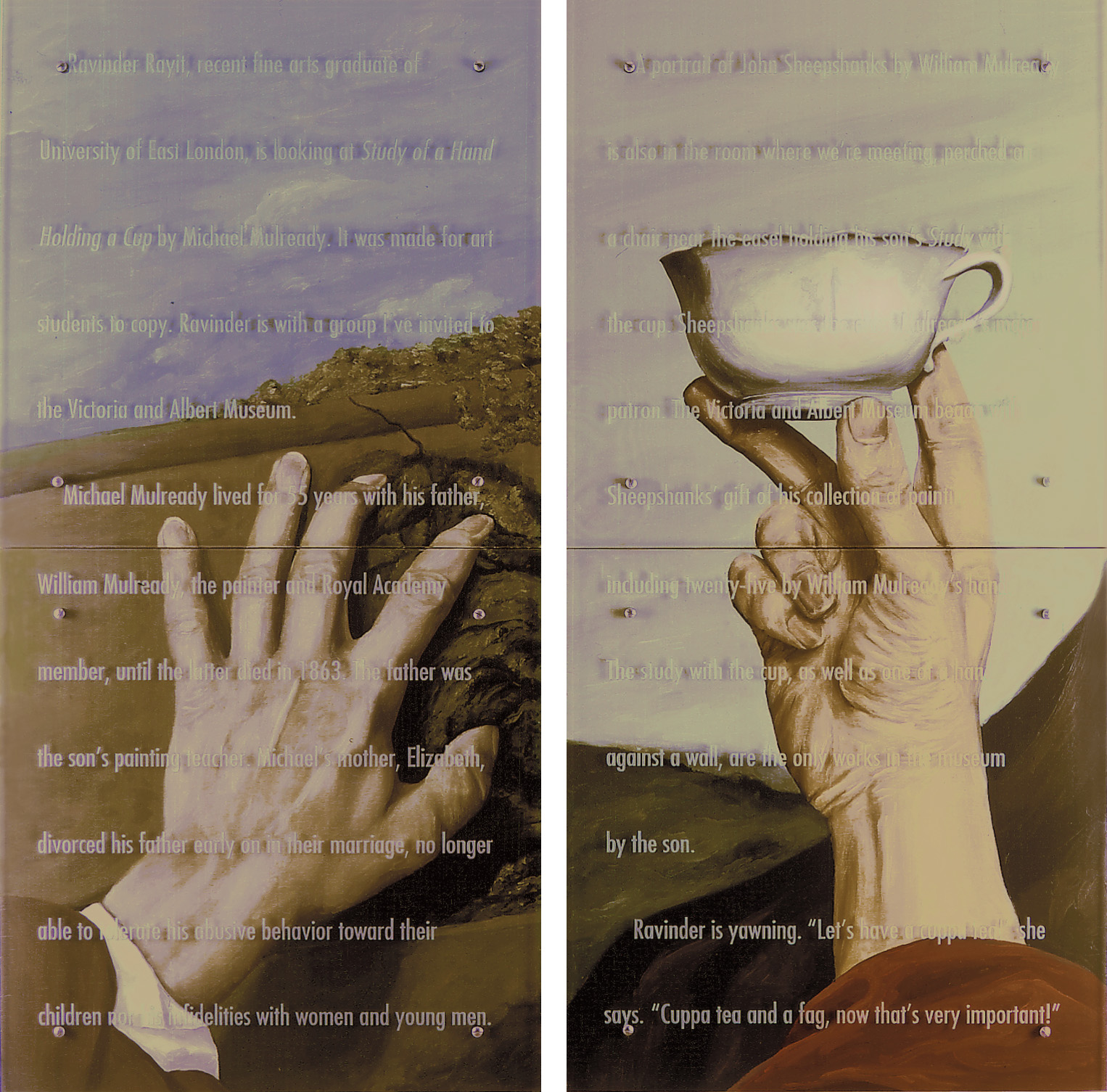

After Michael Mulready (both), Study of a Hand Holding a Cup, V&A , London

TEXT: Ravinder Rayit, recent fine arts graduate of University of East London, is looking at Study of a Hand Holding a Cup by Michael Mulready. It was made for art students to copy. Ravinder is with a group I’ve invited to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Michael Mulready lived for 55 years with his father, William Mulready, the painter and Royal Academy member, until the latter died in 1863. The father was the son’s painting teacher. Michael’s mother, Elizabeth, divorced his father early on in their marriage, no longer able to tolerate his abusive behavior toward their children nor his infidelities with women and young men. A portrait of John Sheepshanks by William Mulready is also in the room where we’re meeting, perched on a chair near the easel holding his son’s Study with the cup. Sheepshanks was the elder Mulready’s major patron. The Victoria and Albert Museum began with Sheepshanks gift of his collection of paintings, including twenty-five by William Mulready’s hand. The study with the cup, as well as

one of a hand against a wall, are the only works in the museum by the son. Ravinder is yawning. “Let’s have a cuppa tea!” she says. “Cuppa tea and a fag, now that’s very important!”

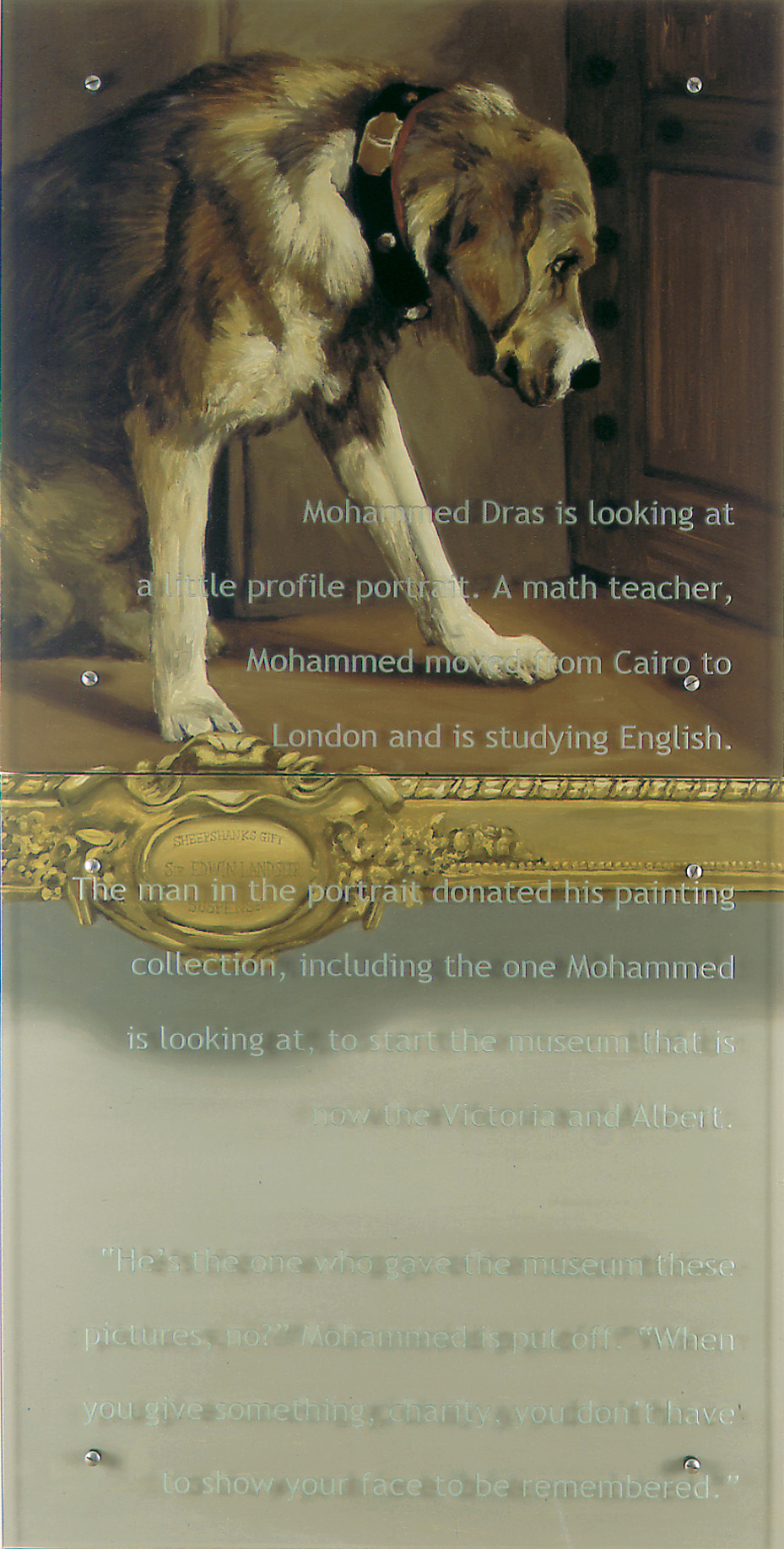

After Edwin Landseer, Suspense, V&A, London

TEXT: Mohammed Dras is looking at a little profile portrait. A math teacher,

Mohammed moved from Cairo to London and is studying English. The man in

the portrait donated his painting collection, including the one Mohammed is

looking at, to start the museum that is now the Victoria and Albert. “He’s the

one who gave the museum these pictures, no?” Mohammed is put off. “When

you give something, charity, you don’t have to show your face to be remembered.”

Mouayed wants the face, 60″ x 60″ (153cm x 153cm) four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts After: Jan Weenix’s The Intruder: Dead Game, Live Poultry and Dog:

Mouayed wants the face, 60″ x 60″ (153cm x 153cm) four panels, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts After: Jan Weenix’s The Intruder: Dead Game, Live Poultry and Dog:TEXT: Mouayed Edeaan wants the face of the vanquished chicken.

I’ve offered to cut out a detail from one of the paintings

we’re looking at in the museum for him to take home.

It’s my way of thanking him for helping me with my artwork.

Mouayed struggles with a learning disability and has

trouble with his balance. He works as a gardener.

“He suffers,” Mouayed observes, “but he…don’t show it.

When you see the head you can imagine the rest. You

know right away that something very…powerful has

gotten him.” I ask, “…has killed him?”

Mouayed: “No, he’s still alive! He…don’t

want to put his face down, don’t want

to show that he’s been hurt.”

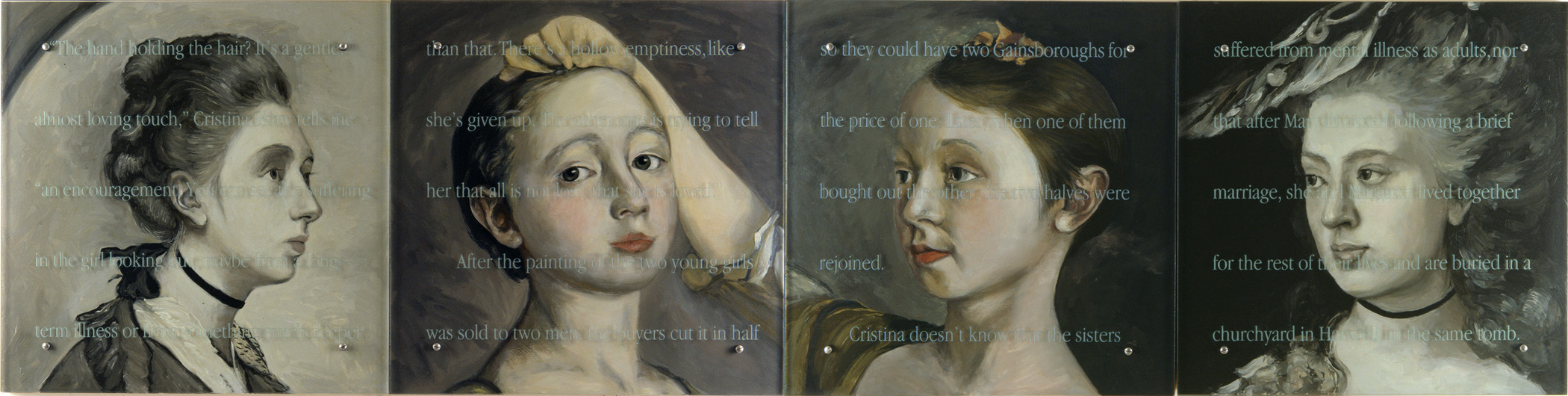

After Gainsborough, The artist’s two daughters, V&A, and his single portraits of daughters Mary and Margaret in the Tate Britain

TEXT: “The hand holding the hair? It’s a gentle, almost loving touch,”

Cristina Shaw tells me, “an encouragement. You can see the suffering in the girl looking out, maybe from a long-term illness or from something much deeper than that. There’s a hollow emptiness, like she’s given up. The other one is trying to tell her that all is not lost, that she is loved.”

After the painting of the two young girls was sold to two men, the buyers cut it in half so they could have two Gainsboroughs for the price of one. Later, when one of them bought out the other, the two halves were rejoined. Cristina doesn’t know that the sisters suffered from mental illness as adults, nor that after Mary divorced following a brief marriage, she and Margaret

lived together for the rest of their lives and are buried in a churchyard in Hanwell, in the same tomb.

After (top to bottom):

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Elizabeth I

(The Ditchley Portrait) c.1592, National Portrait Gallery

Sir Nathaniel Bacon, Self-Portrait, c.1620

Isaac Oliver, The Browne Brothers, 1598, Burghley House Collection

Daniel Mytens, James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, later 1s Duke of Hamilton, 1623, Tate Gallery

TEXT: Edward VI was crowned at age ten. Think back, I tell Olga Sotuela.

You are around his age and you about to become King. What’s your first decree? “When I was young during the Spanish Civil War,” Olga remembers, “my feet were bleeding from having to walk barefoot.” Olga rules. “Shoes for everyone!”

TEXT: At one time the sitter was thought to be Elizabeth Throckmorton, wife of Robert Pemberton. More recently, a new interpretation of the evidence points to a different identity. Hans Holbein painted the miniature in 1540 on the skin of an aborted calf, which was then glued to a five of diamonds for support. Formerly owned by J. Pierpont Morgan, the museum purchased it in 1935 for a fraction of its current value, judging from recent sales of similar works at £6,000,000. What does any of this reveal about the woman? I’m eager to ask what visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum make of her, but worry that such a tiny image is too demanding for them. How much concentration can I expect? Yet this diminutive woman trapped within her circular frame touches me, and I introduce her to the museum visitors. One person thinks she’s been promised in marriage but loves another. Someone else, that she’s a man in drag who’d just like to keep it secret. Another says she’s pregnant, and not by her husband, “Him!” she says, pointing to a miniature by Madame Darbois nearby. A redhead hopes she’s considering fleeing to France to avoid an arranged marriage. From my research I learn the sitter’s name is Jane Small. Nor would it surprise me to discover that her marriage was arranged when her father, playing with her future husband, Nicholas, lost a game of gin rummy.

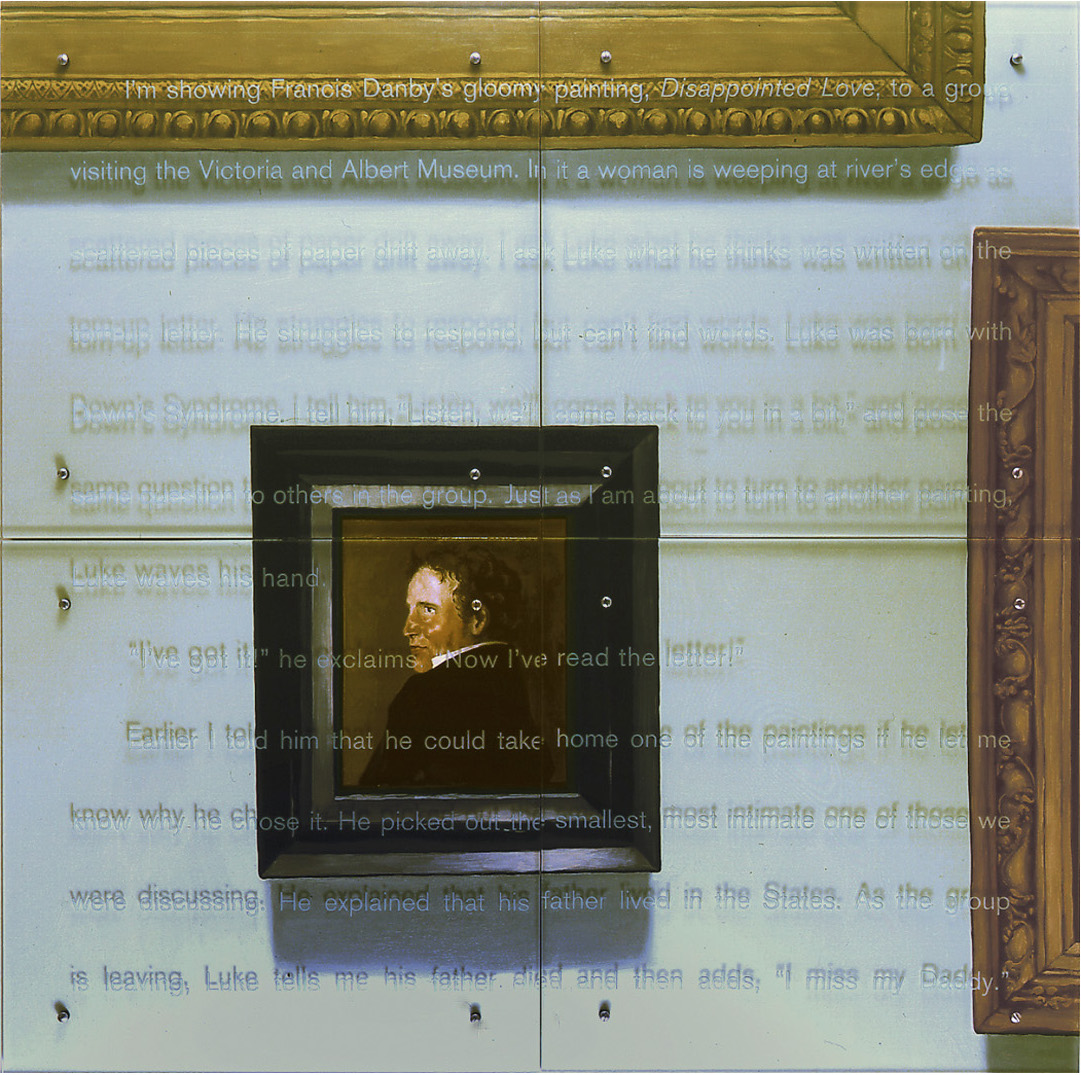

After William Mulready, Portrait of John Sheepshanks, V&A, London, TEXT: I’m showing Francis Danby’s gloomy painting, Disappointed Love, to a group visiting the Victoria and Albert Museum. In it a woman is weeping at river’s edge as scattered pieces of paper drift away. I ask Luke what he thinks was written on the torn-up letter. He struggles to respond, but can’t find words. Luke was born with Down’s Syndrome. I tell him, “Listen, we’ll come back to you in a bit,” and pose the same question to others in the group. Just as I am about to turn to another painting, Luke waves his hand. “I’ve got it!” he exclaims. “Now I’ve read the letter!” Earlier I told him that he could take home one of the paintings if he let me know why he chose it. He picked out the smallest, most intimate one of those we were discussing. He explained that his father lived in the States. As the group is leaving, Luke tells me his father died and then adds, “I miss my Daddy.”

oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

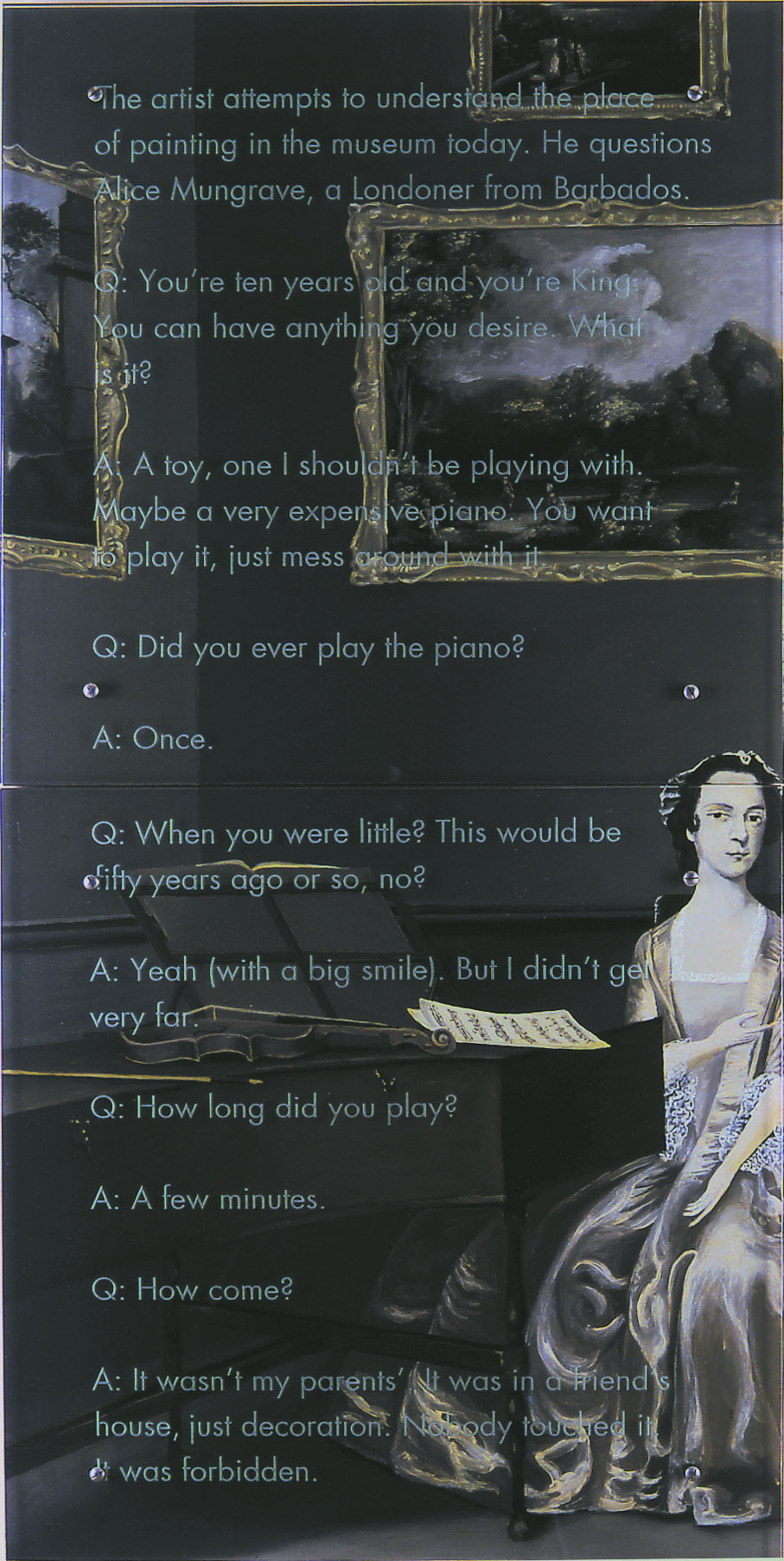

After Arthur Devis, The Duet, 1749, V&A, London

TEXT: The artist attempts to understand the place of painting in the museum today. He questions Alice Mungrave, a Londoner from Barbados. Q: You’re ten years old and you’re King. You can have anything you desire. What is it? A: A toy, one I shouldn’t be playing with. Maybe a very expensive piano. You want to play it, just mess around with it. Q: Did you ever play the piano? A: Once. Q: When you were little? This would be fifty years ago or so, no? A: Yeah (with a big smile). But I didn’t get very far. Q: How long did you play? A: A few minutes. Q: How come? A: It wasn’t my parents. It was in a friend’s house, just decoration. Nobody touched it. It was forbidden.

OTHER WORKS FROM 2000

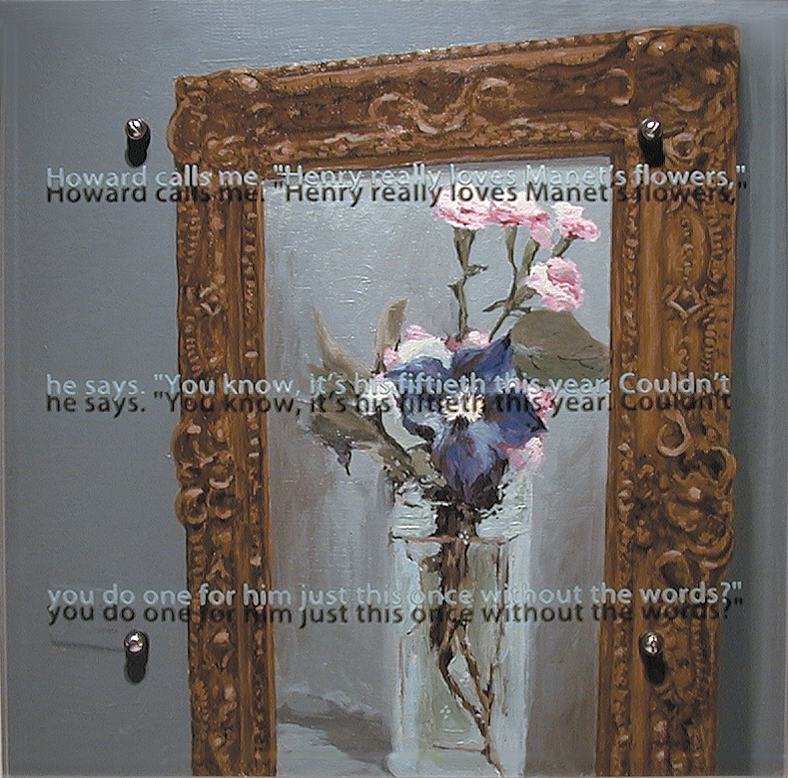

After Edouard Manet, Clematis in a Crystal Vase, c.1881, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France

TEXT: Howard calls me. “Henry really loves Manet’s flowers,” he says. “You know, it’s his 50th this year. Couldn’t you do one for him just this once without the words?”

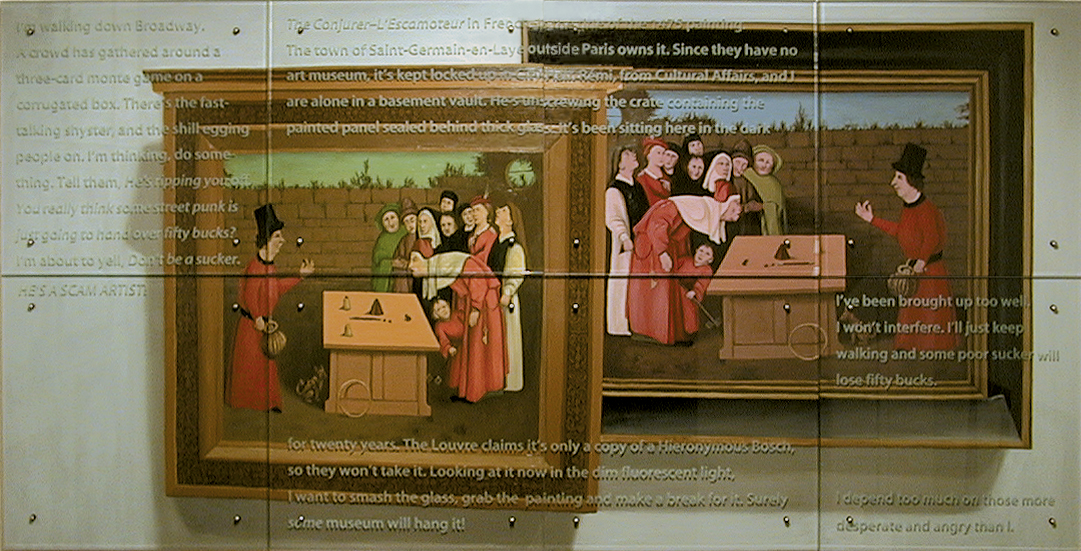

After Hieronymous Bosch, The Conjurer (L’Escamoteur), 1475, Musée Municipale de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

TEXT: I’m walking down Broadway. A crowd has gathered around a three-card monte game on a corrugated box. There’s the fast-talking shyster and the shill egging people on. I’m thinking, do something. Tell them, He’s ripping you off. You really think some street punk is just going to hand over fifty bucks? I’m about to yell, Don’t be a sucker. HE’S A SCAM ARTIST! The Conjurer–L’Escamoteur in French–is the title of the 1475 painting. The town of Saint-Germain-en-Laye outside Paris owns it. Since they have no art museum, it’s kept locked up in City Hall. Rémi, from Cultural Affairs, and I are alone in a basement vault. He’s unscrewing the crate containing the painted panel

sealed behind thick glass. It’s been sitting here in the dark for twenty years. The Louvre claims it’s only a copy of a Hieronymous Bosch, so they won’t take it. Looking at it now in the dim fluorescent light, I want to smash the glass, grab the painting and make a break for it. Surely some museum will hang it! I’ve been brought up too well. I won’t interfere. I’ll just keep walking and some poor sucker will lose fifty bucks. I depend too much on those more desperate and angry than I.

THE FOLLOWING WORKS WERE INCLUDED IN THE 2001 EXHIBITION, ANGELS? at the Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, Miami, FL:

TEXT:

She came to him an angel, sweet and loving.

Did he sense the troubling messages she kept

to herself? Was that what made her an angel?

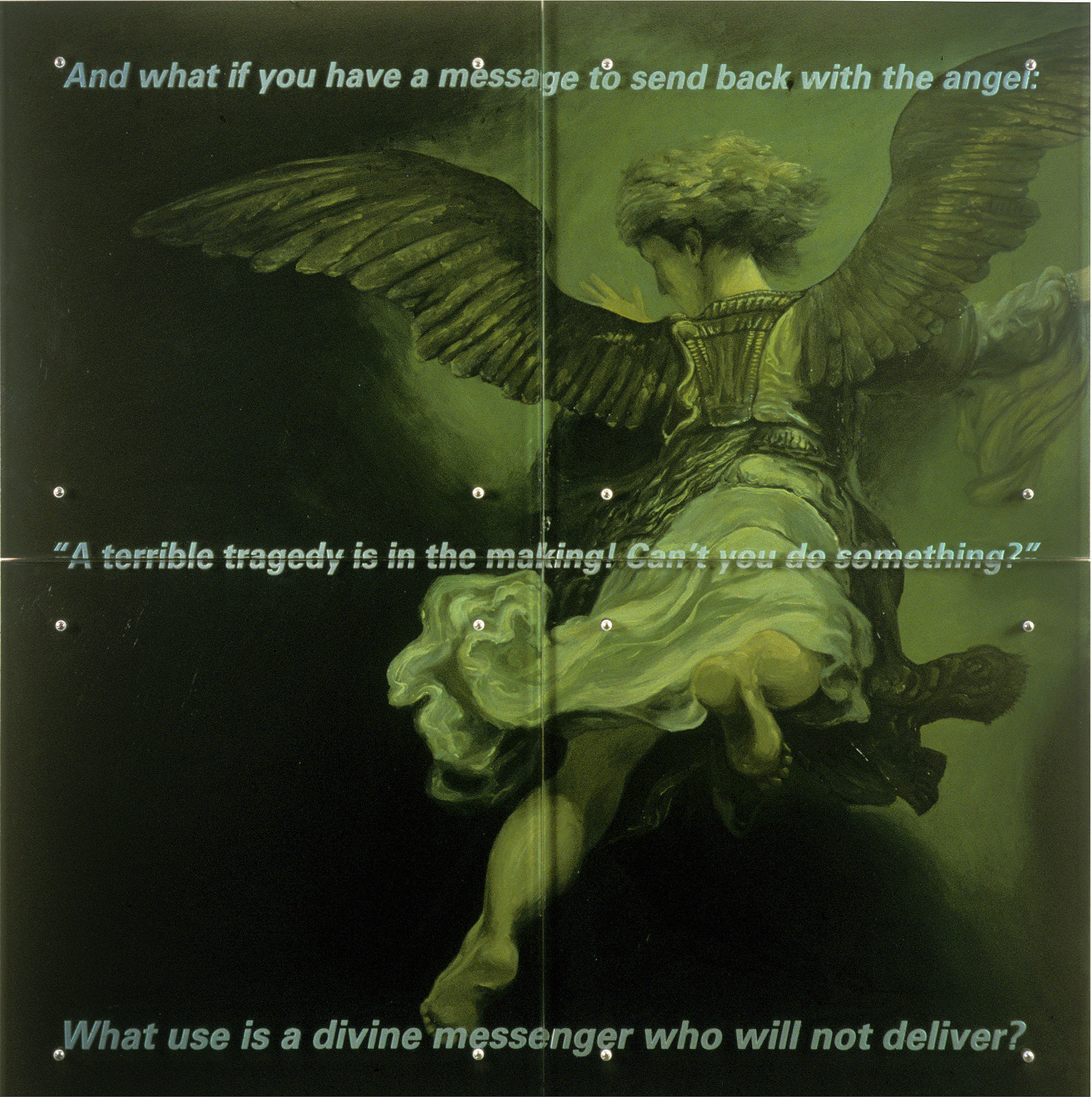

After Fra Angelico, Annunciatory Angel, 1450-55, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan

TEXT: And what if you have a message to send back with the angel: “A terrible tragedy is in the making! Can’t you do something?” What use is a divine messenger who will not deliver?

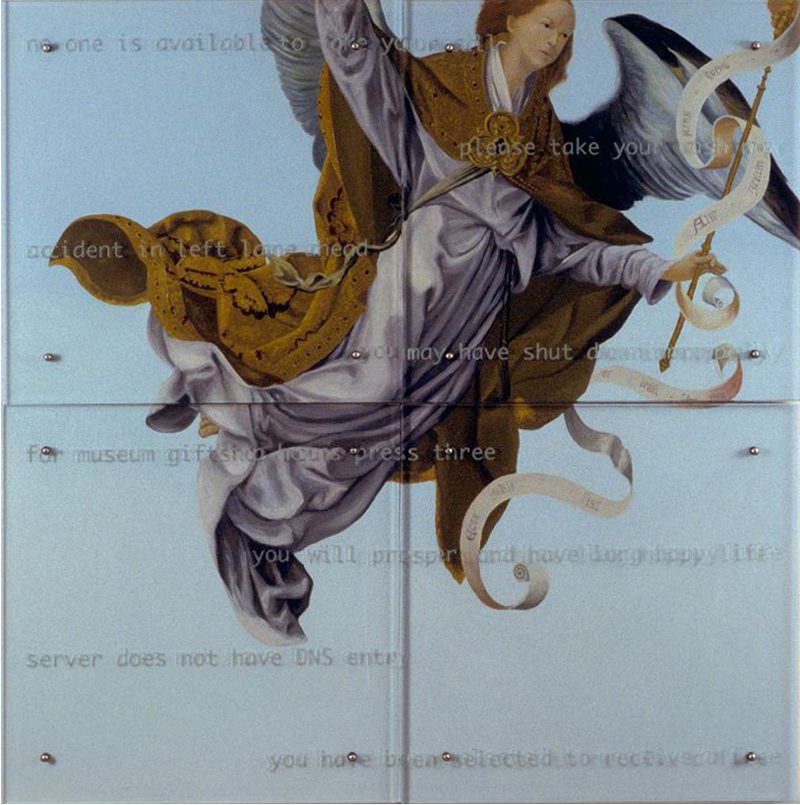

After Rembrandt van Rijn, The angel leaving Tobias and his family, 1637, Louvre, Paris

TEXT: no one is available to take your call

you may have shut down improperly

for museum giftshop hours press three

please enter your pin number

accident in right lane ahead

you will prosper and have long happy life

server does not have DNS entry

seventh floor: intimate apparel, adjustments

After Robert Campin, The Nativity, 1420, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, France

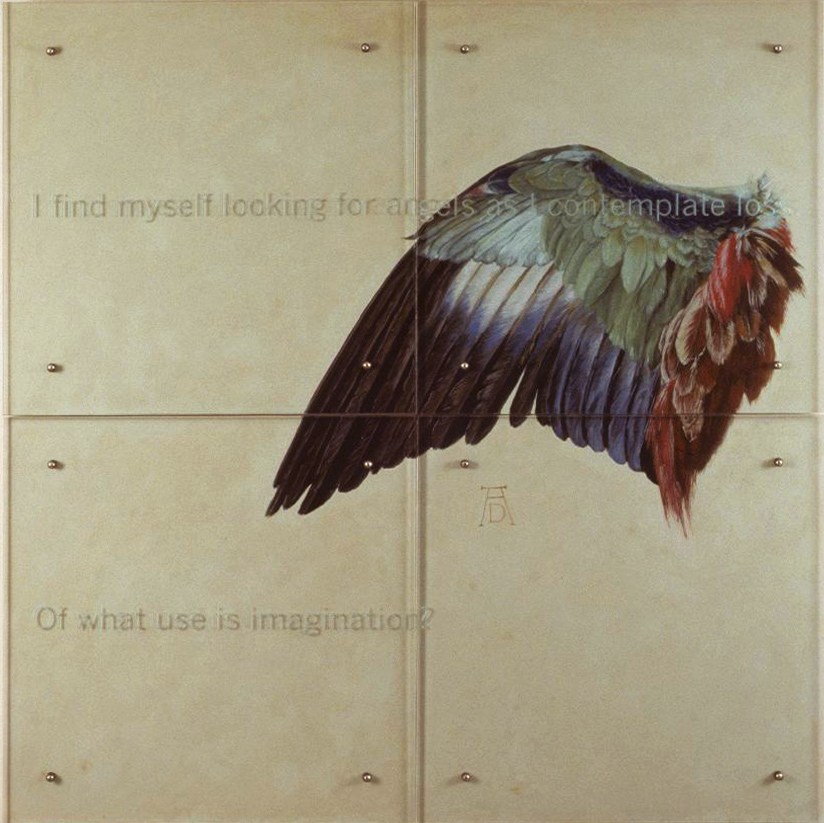

TEXT: I find myself looking for angels as I contemplate loss. Of what use is imagination?

After Albrecht Durer, Wing of a European Roller, 1502-10, Albertina Museum, Vienna

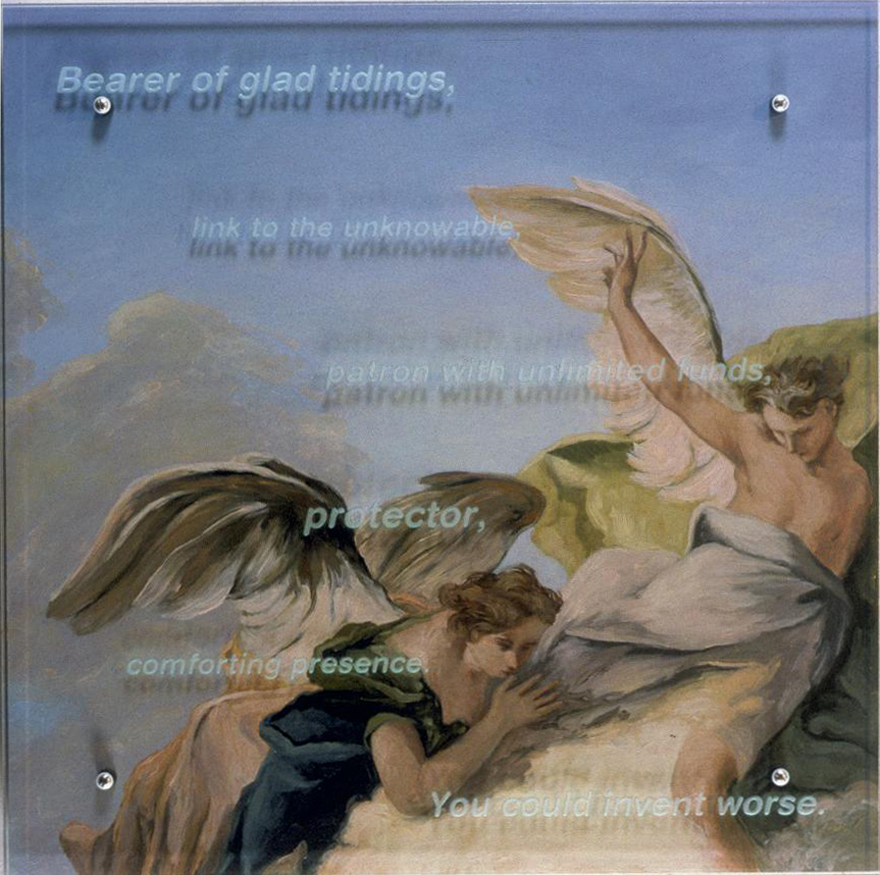

TEXT: Bearer of glad tidings, link to the unknowable, patron with unlimited funds, protector, comforting presence. You could invent worse.

After Giambattista Pittoni, Christ giving the key of Paradise to St. Peter, mid-18th c., Musée du Louvre, Paris

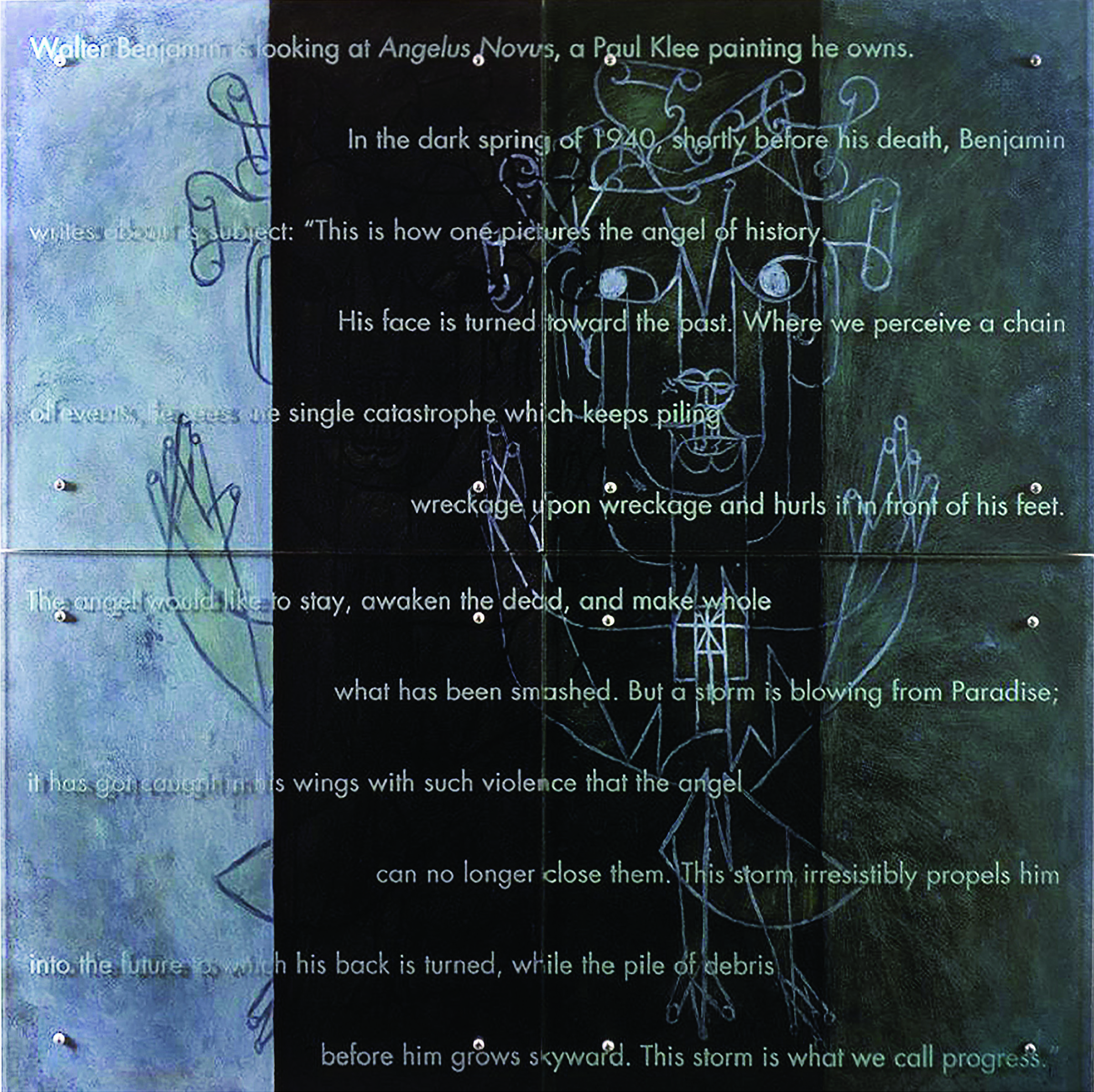

TEXT: Walter Benjamin is looking at Angelus Novus, a Paul Klee painting he owns. In the dark spring of 1940, shortly before his death, Benjamin writes about its subject: “This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

After Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920, Israel Museum, Jerusalem

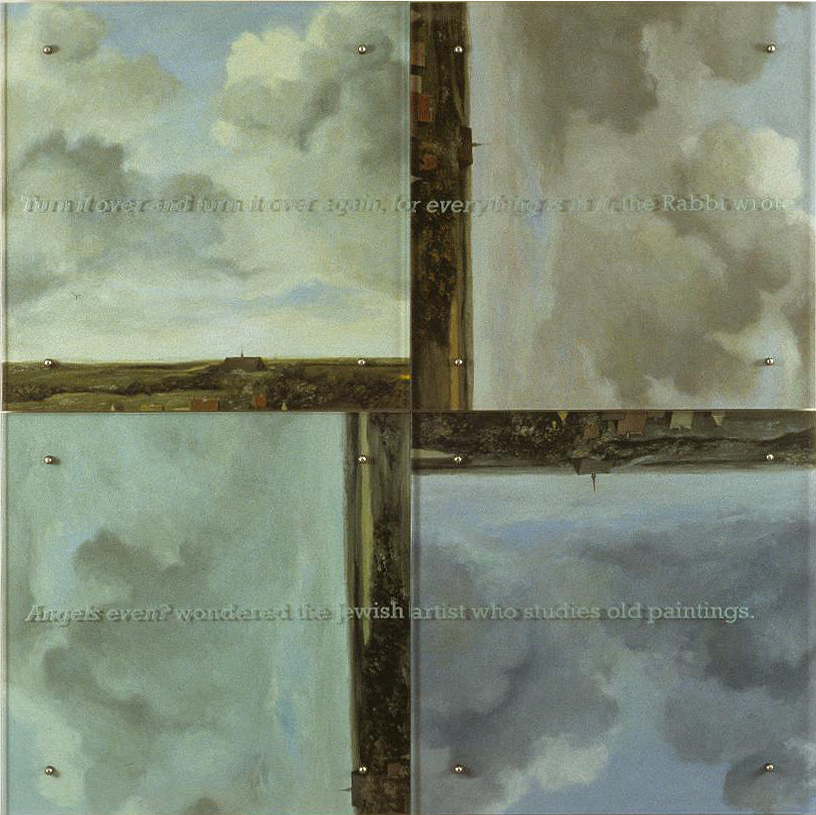

TEXT: Turn it over and turn it over again, for everything is in it, the Rabbi wrote. Angels even? wondered the Jewish artist who studies old paintings.

After Jan van Ruisdael (attributed), Bleaching fields at Bloemendael near Haarlem, c. 1670, Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

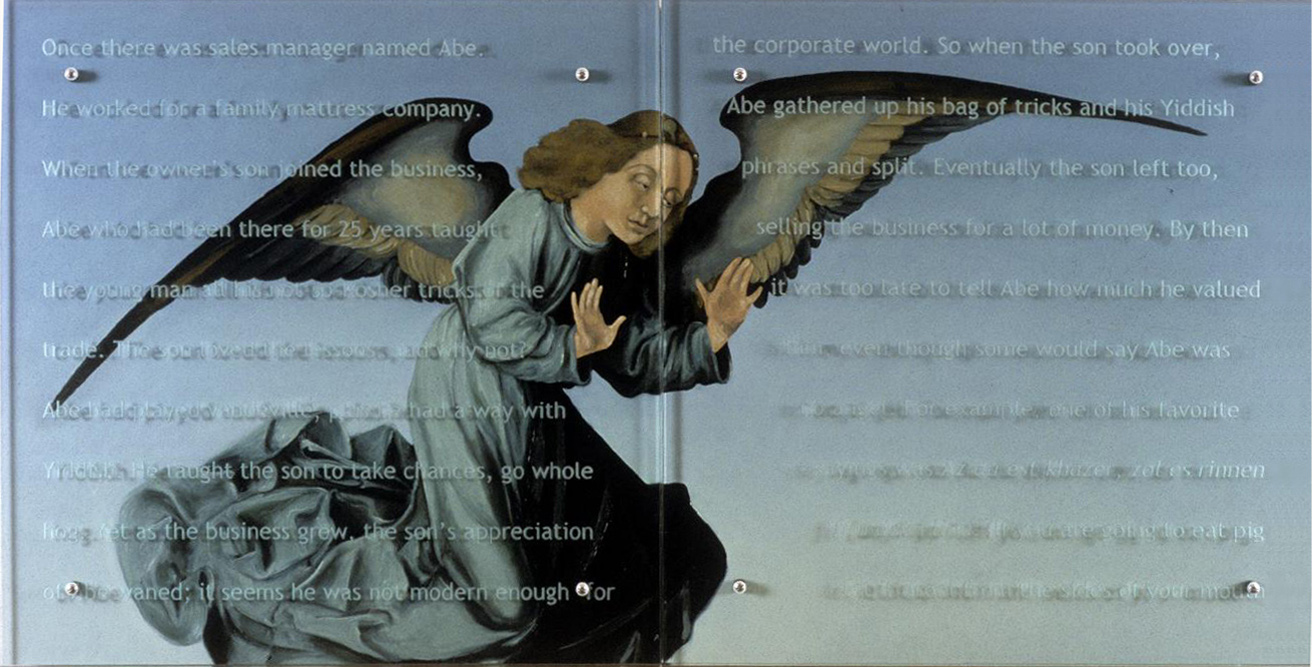

TEXT: Once there was a sales manager named Abe. He worked for a family mattress company. When the owner’s son joined the business, Abe who had been there for 25 years taught the young man all his not-so-Kosher trickes of the trade. The son loved the lessons, and why not? Abe had played vaudeville, plus he had a way with Yiddish. He taught the son to take chances, go whole hog. Yet as the business grew, the son’s appreciation of Abe waned; it seems he was not modern enough for the corporate world. So when the son took over, Abe gathered up his bag of tricks and his Yiddish phrases and split. Eventually the son left too, selling the business for a lot of money. By then it was too late to tell Abe how much he valued him, even though some would say Abe was no angel. For example, one of his favorite sayying was Az du est khazer, zol es rinnen fun dayn lipn. (If you are going to eat pig, let it drool from the sides of your mouth.)

After Justus of Ghent, The Communion of the Apostles, 1550?, Palazzo Ducal, Urbino, Italy

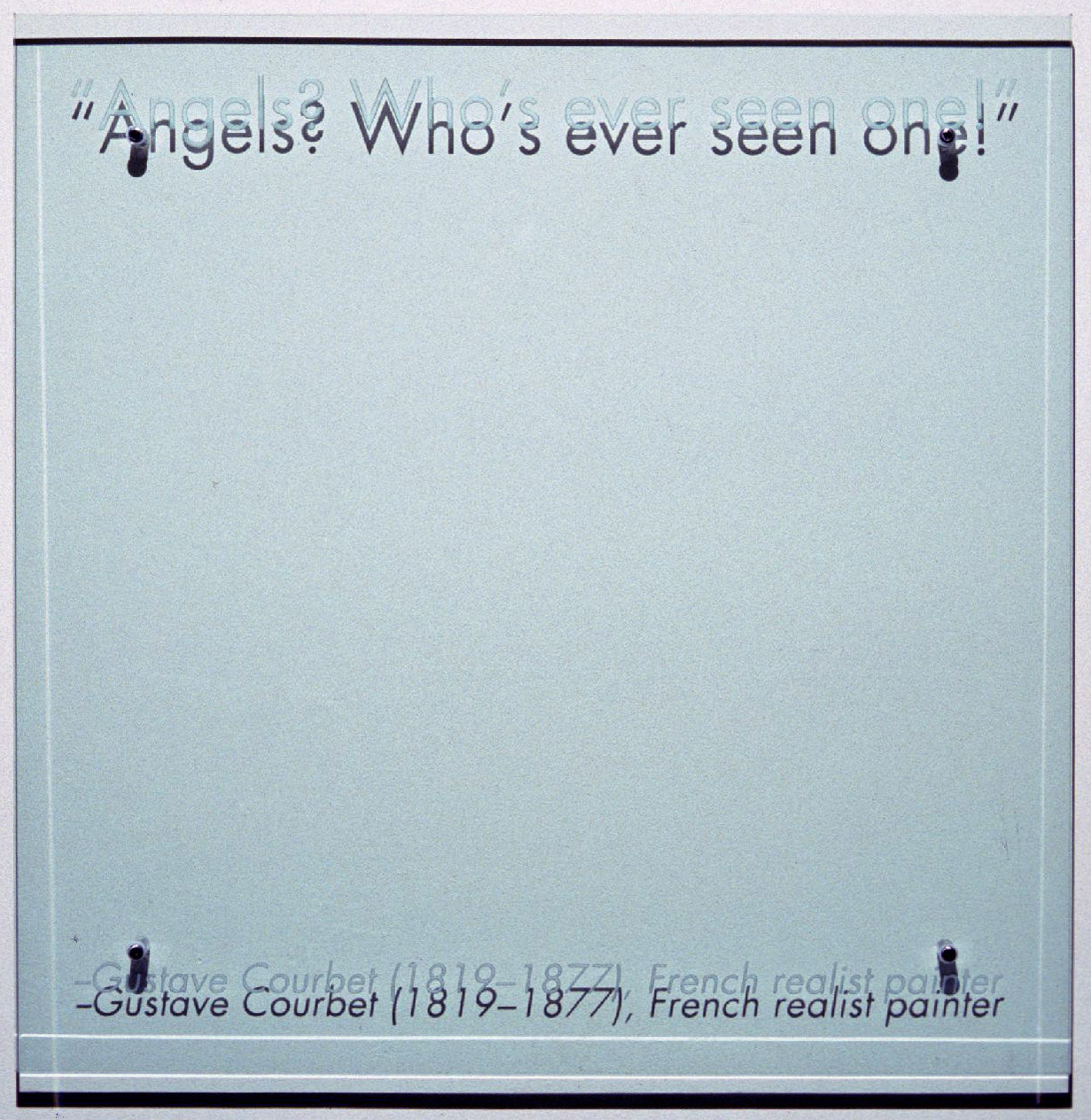

TEXT: “Angels? Who’s ever seen one!”

–Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), French realist painter

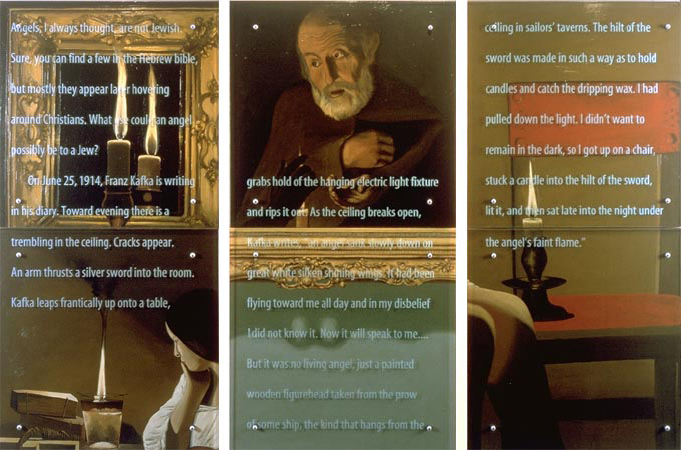

TEXT: Angels, I always thought, are not Jewish.

Sure, you can find a few in the Hebrew bible, but mostly they appear later hovering around Christians. What use could an angel possibly be to a Jew? On June 25, 1914, Franz Kafka is writing in his diary. Toward evening there is a trembling in the ceiling. Cracks appear. An arm thrusts a silver sword into the room. Kafka leaps frantically up onto a table, grabs hold of the hanging electric light fixture and rips it out. As the ceiling breaks open, Kafka writes, “an angel sank slowly down on great white silken shining wings. It had been flying towards me all day and in my disbelief I did not know it. Now it will speak to me…. But it was no living angel, just a painted wooden figurehead taken from the prow of some ship, the kind that hangs from the ceiling in sailors’ taverns. The hilt of the sword was made in such a way as to hold candles and catch the dripping wax. I had pulled down the light. I didn’t want to remain in the dark, so I got up on a chair, stuck a candle into the hilt of the sword, lit it, and then sat late into the night under the angel’s faint flame.”

After (left to right) Georges de la Tour (all),

The Magdalene with two flames, c. 1640-44, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

The denial of St. Peter, 1650, Musée des Beaux Arts, Nantes, France

The repentant Magdalene, c.1640, Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Magdalene and the smoking flame, c.1636-38, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

The flea catcher, c. 1630-34, Musée Historique Lorrain, Nancy, France

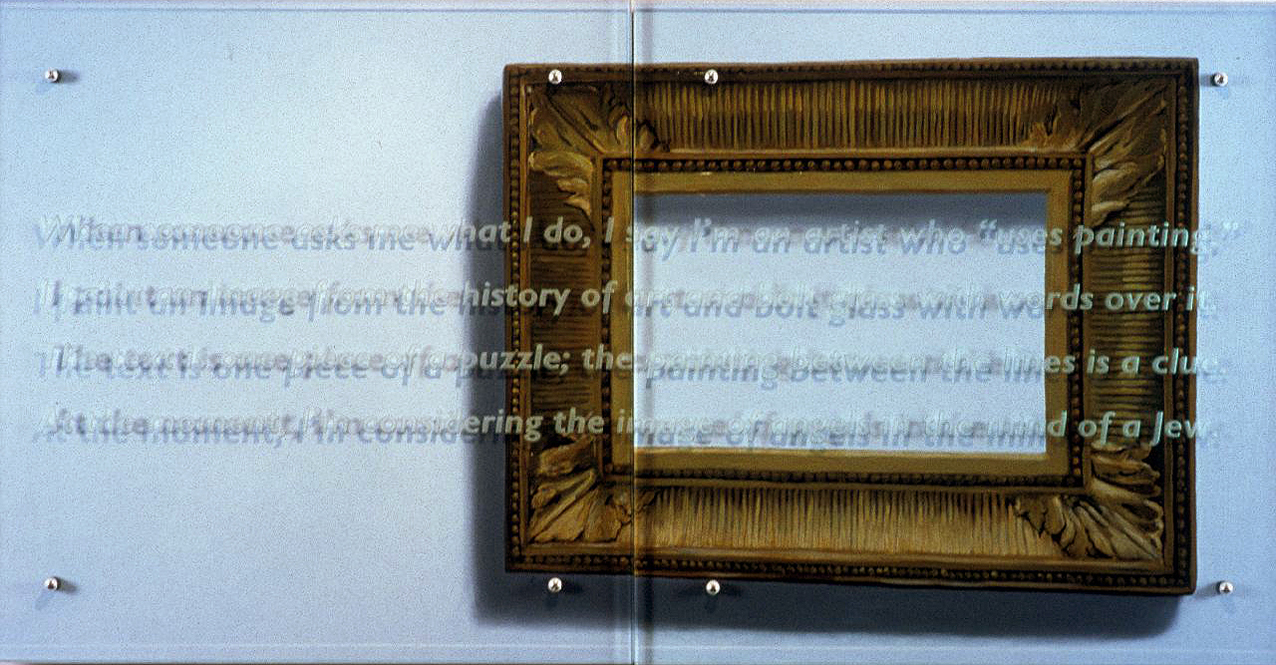

TEXT: When someone asks me what I do, I say I’m an artist who “uses painting.” I paint an image from the history of art and bolt glass with words over it. The text is one piece of a puzzle; the painting between the lines is a clue. At the moment, I’m considering the image of angels in the mind of a Jew.