![Haven't I seen you in a painting? 70" x 35" diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts After Jonas Lie, Morning on the River, 1913 and Kathleen McEnery [Cunningham], Woman in an Ermine Collar, 1909 Text: I need a title for my painting, so I ask Joe. But I'm indirect; it's my nature. Rather than come right out and say what I want, I show Joe some paintings in a museum and we talk about them. I say, Where would you put yourself in Jonas Lie's Morning on the River? Next to the woman standing alone on the pier Joe responds. I ask, Do you have a line ready? He says he's working on it. Later we look at Kathleen McEnery's Woman with an Ermine Collar. It reminds me of my mother. She studied art when she was a girl, taught art briefly before starting a family. You could look at her every day and wonder, says Joe with a sigh. Ask an indirect question, get an indirect answer: Haven't I seen you in a painting?](http://kenaptekar.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Havent-I-seen-you...jpg)

70″ x 35″ diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

After Jonas Lie, Morning on the River, 1913 and

Kathleen McEnery [Cunningham], Woman in an Ermine Collar, 1909

TEXT: I need a title for my painting, so I ask Joe. But I’m indirect; it’s my nature. Rather than come right out and say what I want, I show Joe some paintings in a museum and we talk about them. I say, Where would you put yourself in Jonas Lie’s Morning on the River? Next to the woman standing alone on the pier Joe responds. I ask, Do you have a line ready? He says he’s working on it. Later we look at Kathleen McEnery’s Woman with an Ermine Collar. It reminds me of my mother. She studied art when she was a girl, taught art briefly before starting a family. You could look at her every day and wonder, says Joe with a sigh. Ask an indirect question, get an indirect answer: Haven’t I seen you in a painting?

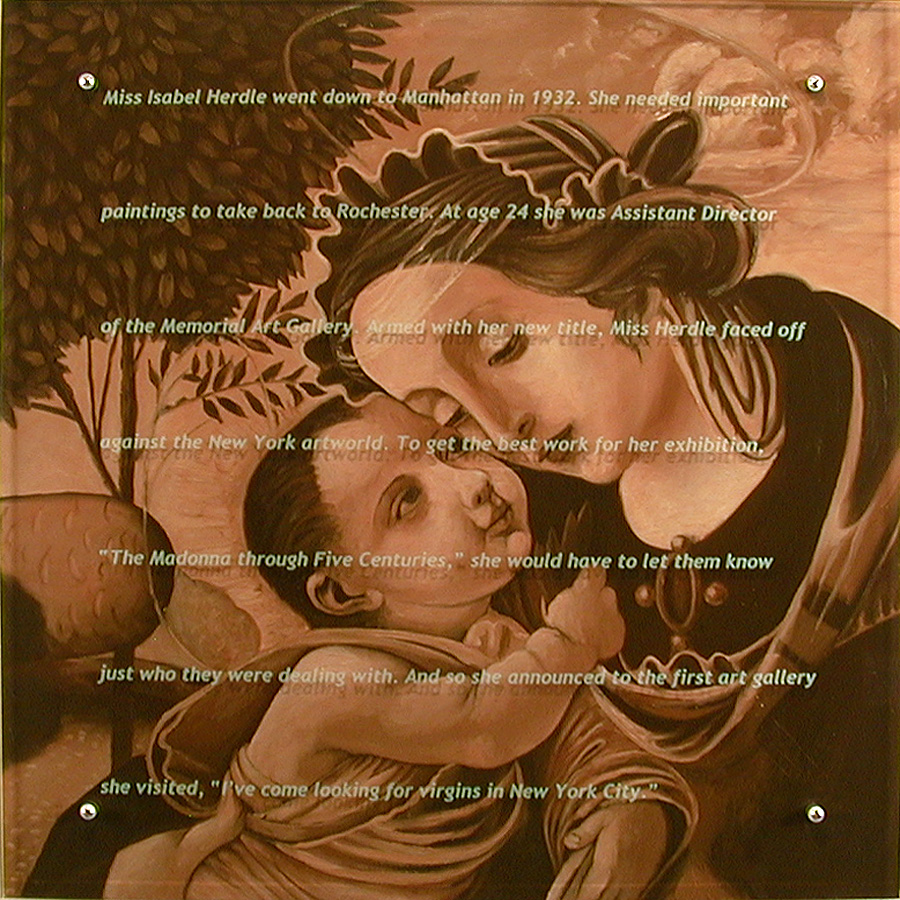

After Raffaellino Del Garbo, Madonna and Child with Angel, ca. 1500

TEXT: Miss Isabel Herdle went down to the big city in 1931. She needed Important Paintings to take back to Rochester. At the age of 24, she was already assistant director of the Memorial Art Gallery there. One can only imagine the difficult time back then a young professional woman had being taken seriously. Miss Herdle would need to pack away her fears, doubts, and pain at the inevitable insults hurled at her by the sophisticated, snooty, and male New York artworld. To get the best work for her exhibition, The Madonna through Five Centuries, she would have to let them know just who they were dealing with. And so in 1931 she announced to the first art gallery she visited, I’ve come looking for virgins in New York City.

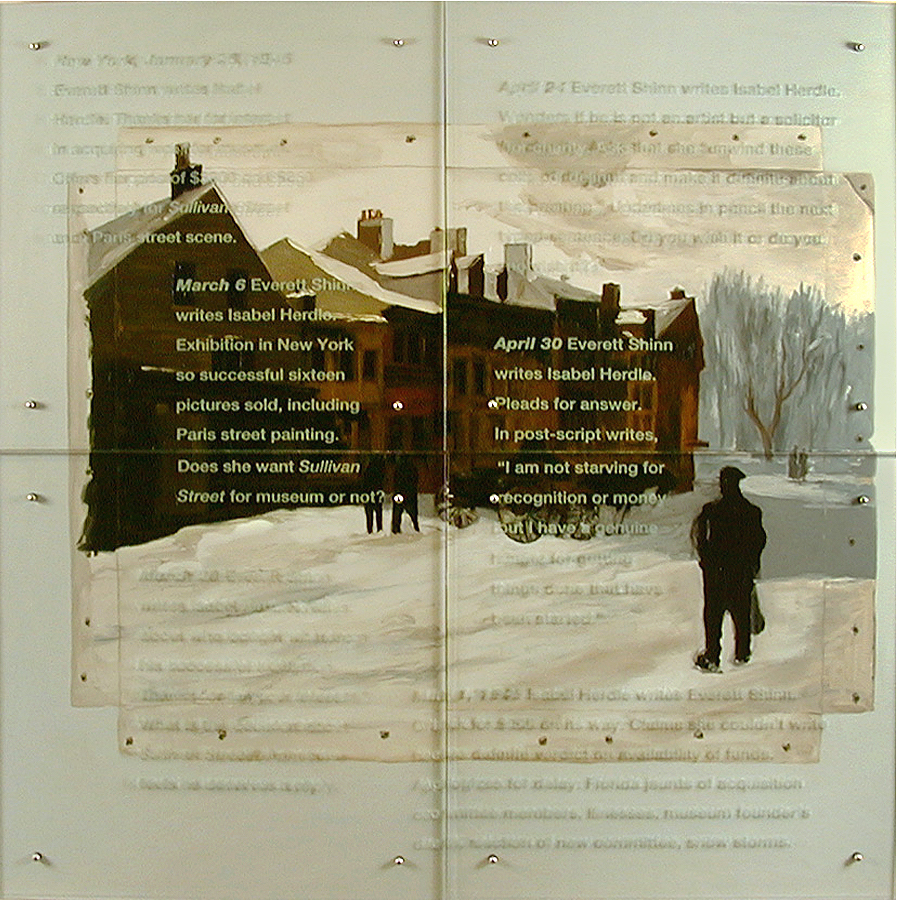

TEXT: Winter, New York, January 25, 1945 Everett Shinn writes Isabel Herdle. Responds to museum’s interest in acquiring two of his works. Offers her Sullivan Street and a Paris street scene, for $300 and $250 respectively. Takes entire single-spaced typed page to do so. March 6 Everett Shinn writes Isabel Herdle. Exhibition in New York so successful sixteen pictures sold, including Paris street painting. Does she want Sullivan Street for museum or not? March 20 Everett Shinn writes Isabel Herdle. News about who bought what from his successful exhibition. Thanks for all your interest. What is the decision about Sullivan Street? Admits he feels he deserves a reply. April 24 Everett Shinn writes Isabel Herdle. Wonders if he is not an artist but a solicitor for charity. Asks that she unwind these coils of delirium and make it definite about the painting. Underlines in pencil the next typed sentence: Do you wish it or do you not wish it? April 30 Everett Shinn writes Isabel Herdle. Pleads for answer. In post-script writes, I am not starving for recognition or money but I have a genuine hunger for getting things done that have been started. May 1, 1945 Everett Shinn gets letter from Isabel Herdle. Check for $300 on

its way. Claims she couldn’t write before definite verdict on availability of funds. Apologizes for delays: Florida jaunts of committee members, illnesses, museum founder’s death, election of new committee, snow storms.

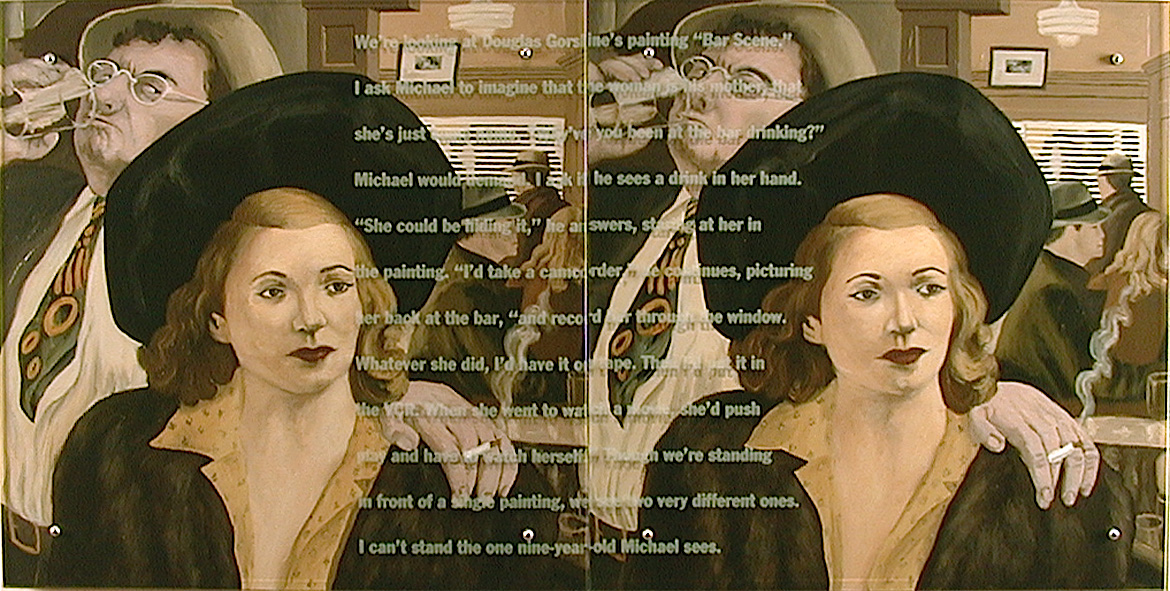

After Douglas Gorsline, Bar Scene, 1942

TEXT: We’re looking at Douglas Gorsline’s painting Bar Scene. I ask Michael to imagine that the woman is his mother, that she’s just come home. “Why’ve you been at the bar drinking?” Michael would demand. I ask if he sees a drink in her hand. “She could be hiding it,” he answers, staring at her in the painting. “I’d take a camcorder,” he continues, picturing her back at the bar, “and record her through the windeow. Whatever she did, I;d have it on tape. Then I’d put it in the VCR. When she went to watch a movie, she’d push play and have to watch herself.” Though we’re standing in front of a single painting, we see two very different ones. I can’t stand the one nine-year-old Michael sees.

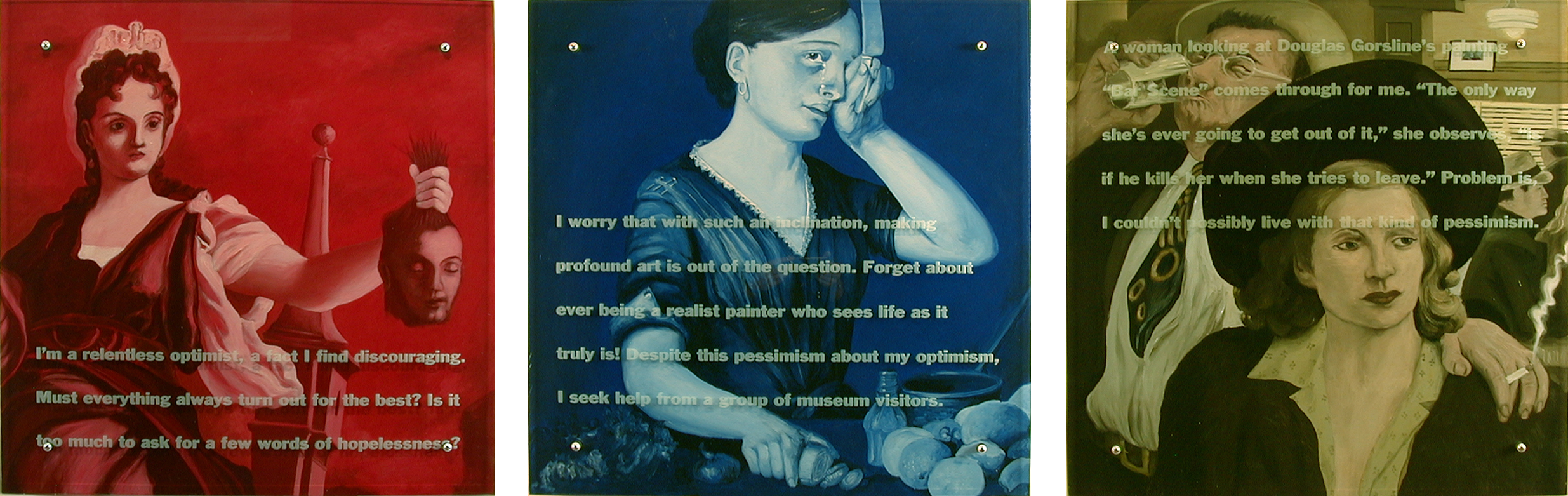

After Francesco Solimena, The Triumph of Judith, ca. 1725-30 and

Lilly Martin Spencer, Peeling Onions, ca. 1852 and Douglas Gorsline, Bar Scene, 1942

TEXT: I’m a relentless optimist, a fact I find discouraging. Must everything always turn out for the best?Is it too much to ask for a few words of hopelessness? I worry that with such an inclination, making profound art is beyond my grasp. Forget about ever being a realist painter who sees life as it truly is! Despite this pessimism about my optimism, I seek help from a group of museum visitors. A woman looking at Douglas Gorsline’s painting Bar Scene comes through for me. The only way she’s ever going to get out of it, she says, is if he kills her when she tries to leave. Problem is, I couldn’t possibly live with that kind of pessimism.

![Those Glasses, 2001 70" x 35" diptych, oil/wood, sandblasted glass, bolts After John James Audubon [attributed], Colonel Nathaniel Rochester, ca. 1824 Text: What makes a painting memorable? It's hardly noteworthy that Colonel Rochester seems cheerless, or that his portrait is said to have been painted by John James Audubon, later famous for bird paintings. Even if you live in Rochester, I doubt you care much about a picture of its scowling founder. But then, there are those glasses. Oddly prophetic, isn't it, that this man's town became world-famous for its optical inventions? Pat Peterson, a guard at the museum that owns the painting says, "Big deal, he can afford fancy bifocals! He couldn't get good dental work." I ask my dentist friend Elie Malka in Paris to have a look. "You see his jaw muscles? Elie observes. "Powerful. He grinds his teeth. He's worn them down so much the face is collapsing between the nose and chin. The guy is tense, very tense." If the Colonel had not been wearing glasses, I wonder, would Rochester have become world-famous for dentistry?](http://kenaptekar.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Thoseglasses.jpg)

After John James Audubon [attributed], Colonel Nathaniel Rochester, ca. 1824

TEXT: What makes a painting memorable? It’s hardly noteworthy that Colonel Rochester seems cheerless, or that his portrait is said to have been painted by John James Audubon, later famous for bird paintings. Even if you live in Rochester, I doubt you care much about a picture of its scowling founder. But then, there are those glasses. Oddly prophetic, isn’t it, that this man’s town became world-famous for its optical inventions? Pat Peterson, a guard at the museum that owns the painting says, “Big deal, he can afford fancy bifocals! He couldn’t get good dental work.” I ask my dentist friend Elie Malka in Paris to have a look. “You see his jaw muscles? Elie observes. “Powerful. He grinds his teeth. He’s worn them down so much the face is collapsing between the nose and chin. The guy is tense, very tense.” If the Colonel had not been wearing glasses, I wonder, would Rochester have become world-famous for dentistry?