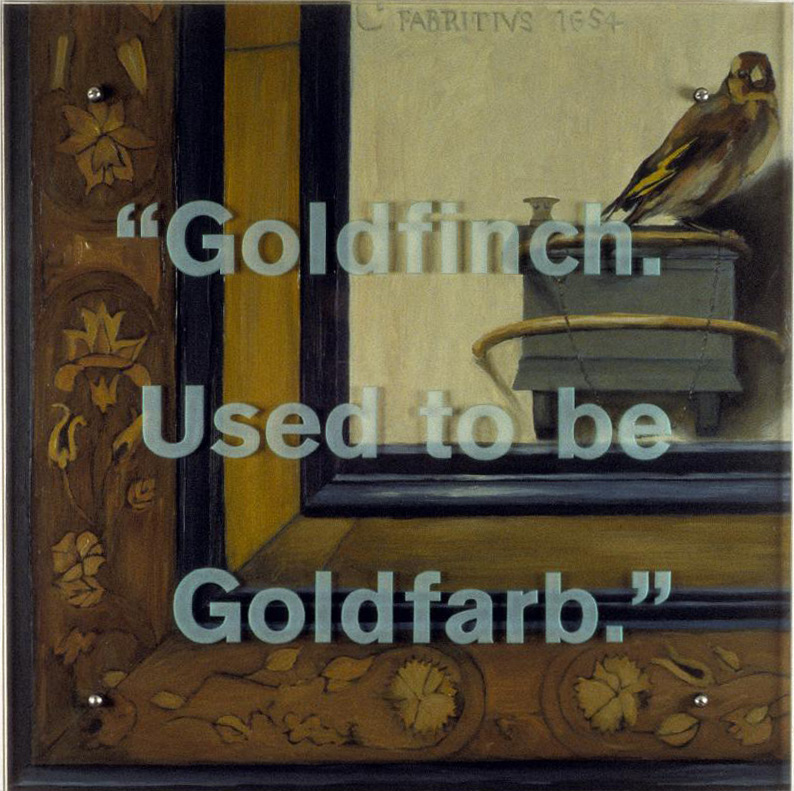

After Carel Fabritius (1622-1654), The Goldfinch

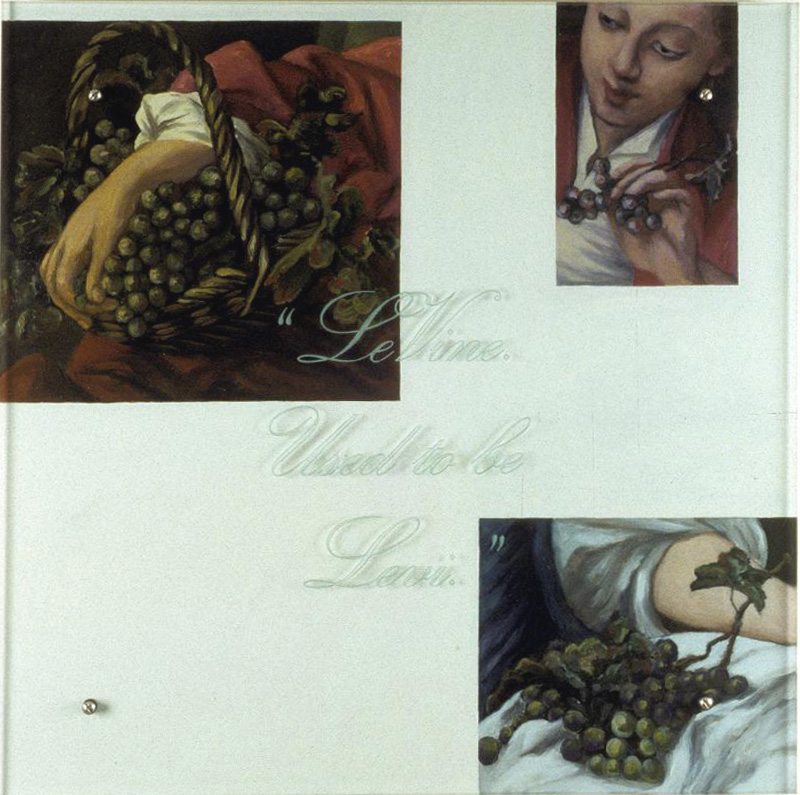

After Francois Boucher, Autumn Pastoral, 1749

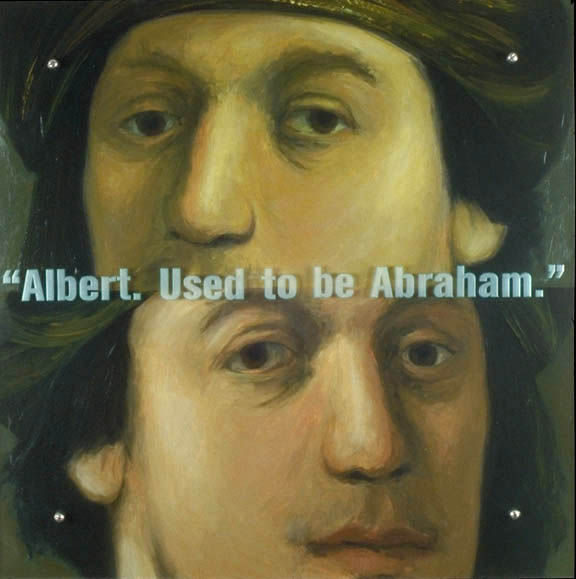

After Isaack Jouderville (student of Rembrandt), Portrait of a man in a turban, 1630-1

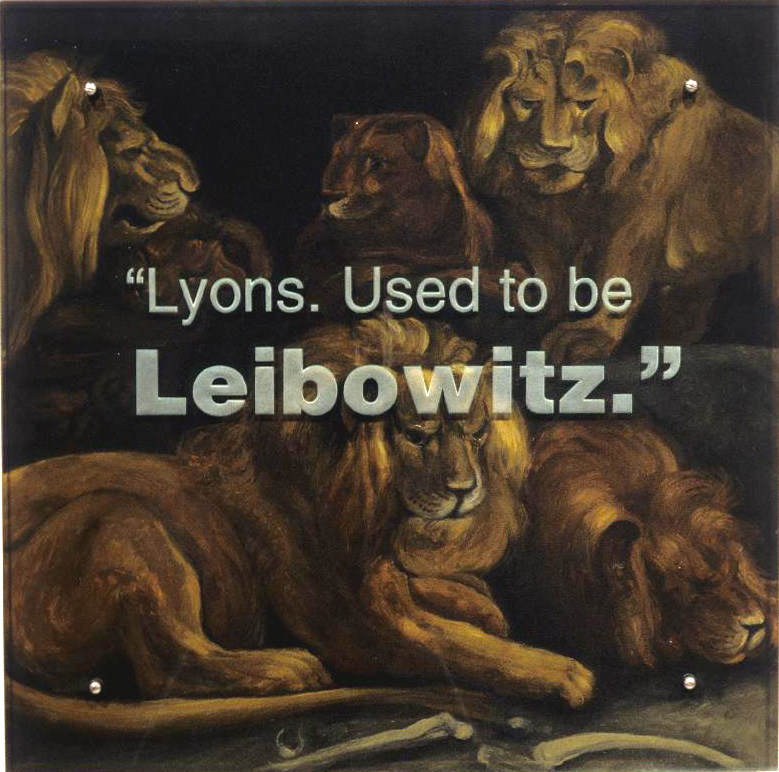

After Peter Paul Rubens, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, c. 1615

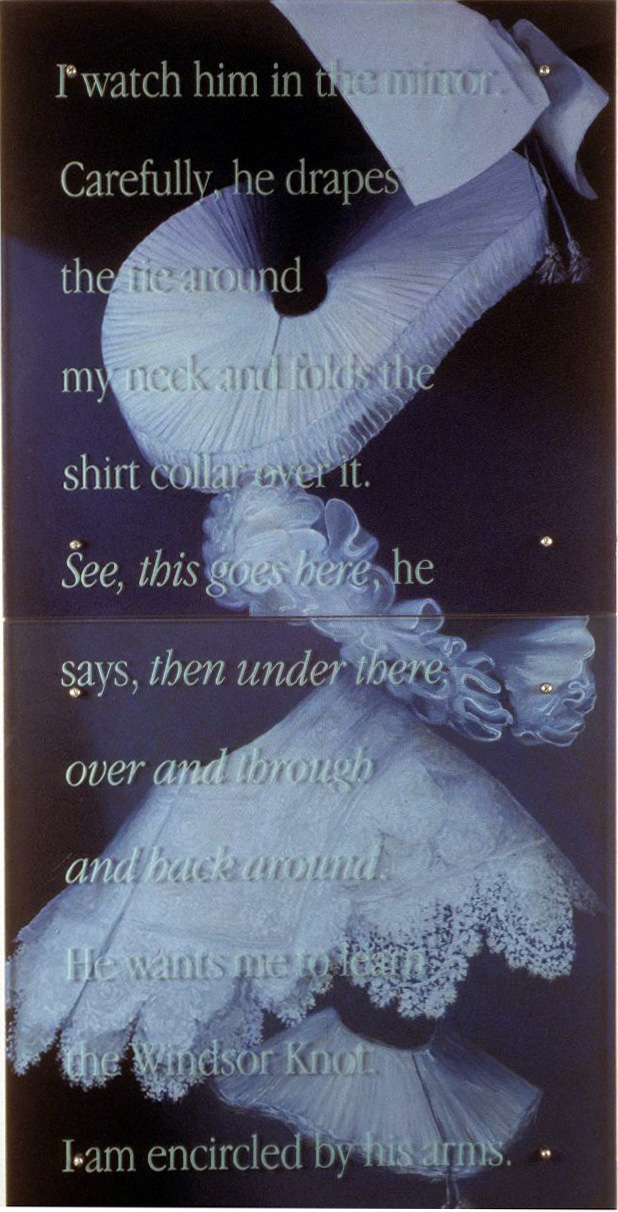

All of the ruffled collars in this painting were based on those worn by subjects of portraits by Rembrandt.

TEXT:

I watch him in the mirror. Carefully, he drapes the tie around my neck and folds the shirt collar over it. See, this goes here, he says, then under there, over and through and back around. He wants me to learn the Windsor Knot. I am encircled by his arms.

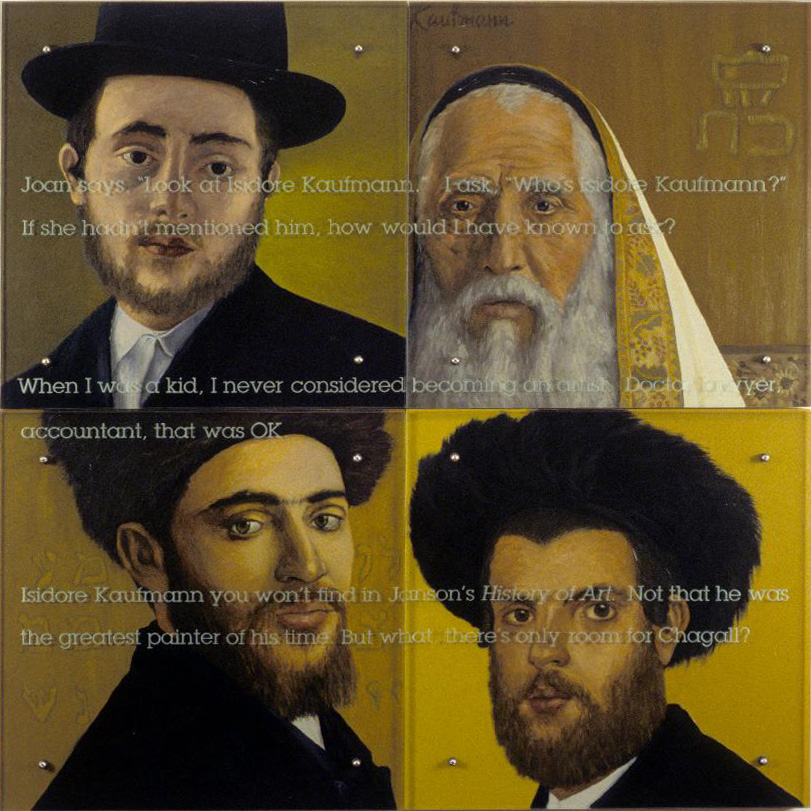

After Isidore Kaufmann, 1853-1921:

Upper left: Young Man with Fedora, c. 1900/01

Upper right: Rabbi with Prayer Shawl

Lower left: Man with Fur Hat

Lower right: Portrait of a Young Hassidic Jew

TEXT:

Joan says, ÒLook at Isidore Kaufmann.Ó I ask, ÒWhoÕs Isidore Kaufmann?Ó If she hadnÕt mentioned him, how would I have known to ask?

When I was a kid, I never considered becoming an artist. Doctor, lawyer, accountant, that was OK.

Isidore Kaufmann you wonÕt find in JansonÕs History of Art. Not that he was the greatest painter of his time. But what, thereÕs only room for Chagall?

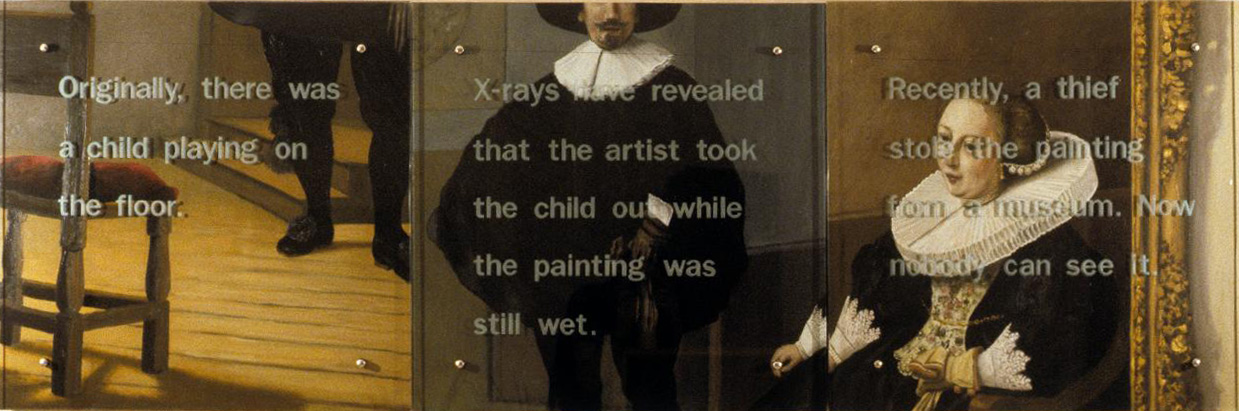

After Rembrandt, Jan Pietersz. Bruyningh and Hillegont Pieters Moutmaker, 1633, Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (stolen, whereabouts unknown)

TEXT:

Originally there was a child playing on the floor. X-rays have revealed that the artist took the child out while the painting was still wet. Recently a thief stole the painting from a museum. Now nobody can see it.

60″ x 90″ (153cm x 229.5cm)

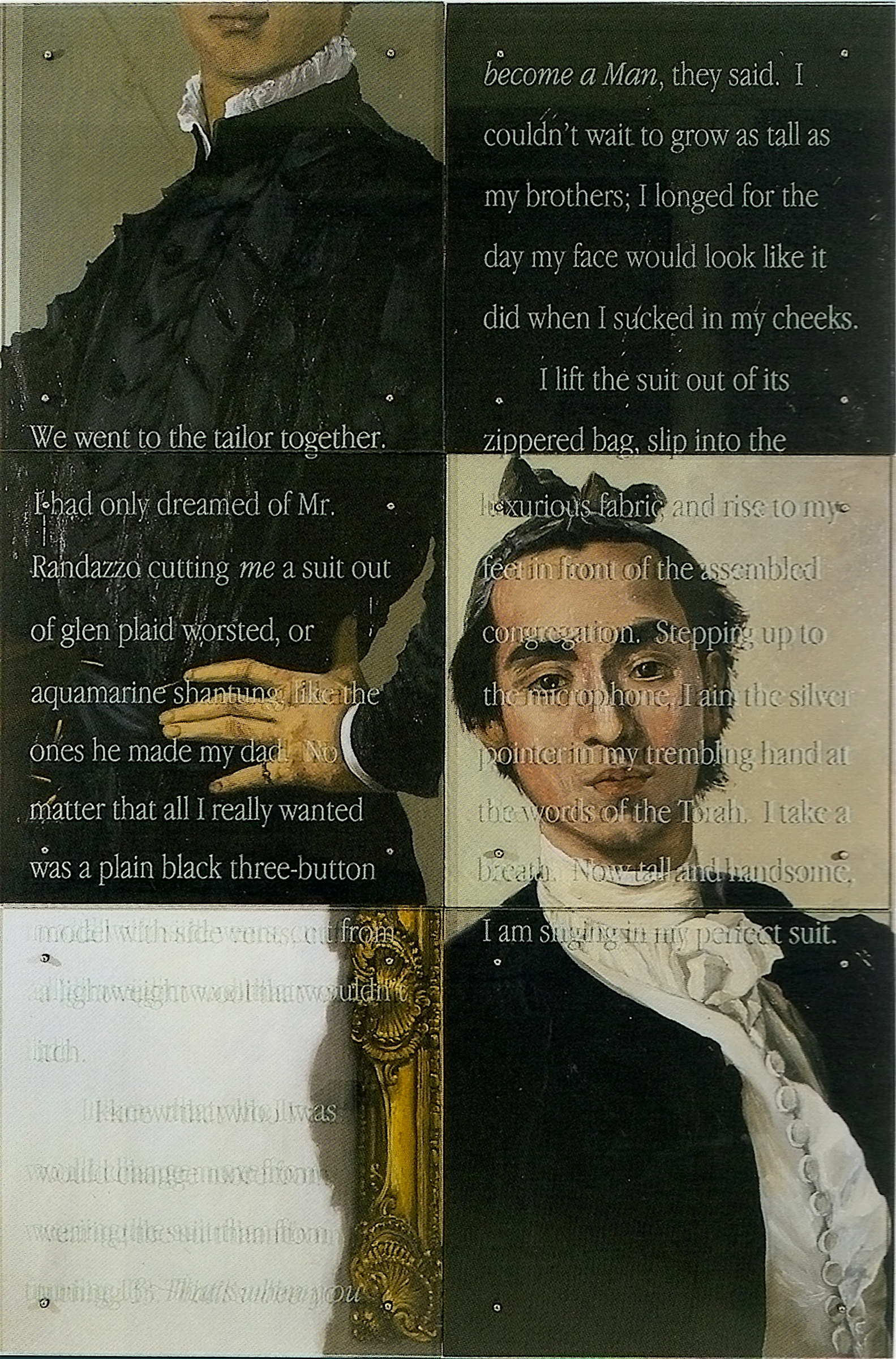

Six panels, oil on wood, sandblasted glass, bolts

After Bronzino (1503-1572), Portrait of a Young Man, and

Luis Eugenio Melendez (1716-1780), Portrait of the artist

holding a life study

TEXT: We went to the tailor together. I had only dreamed of

Mr. Randazzo cutting me a suit out of glen plaid worsted, or

aquamarine shantung, like the ones he made my dad. No matter

that all I really wanted was a plain black three-button model with

side vents, cut from a lightweight wool that wouldn’t itch. I knew

that who I was would change more from wearing the suit than

from turning 13. That’s when you become a Man, they said. I

couldn’t wait to grow as tall as my brothers; I longed for the day

my face would look like it did when I sucked in my cheeks. I lift the

suit out of its zippered bag, slip into the luxurious fabric, and rise

to my feet in front of the assembled congregation. Stepping up to

the microphone, I aim the silver pointer in my trembling hand at the

words of the Torah. I take a breath. Now tall and handsome, I am

singing in my perfect suit.

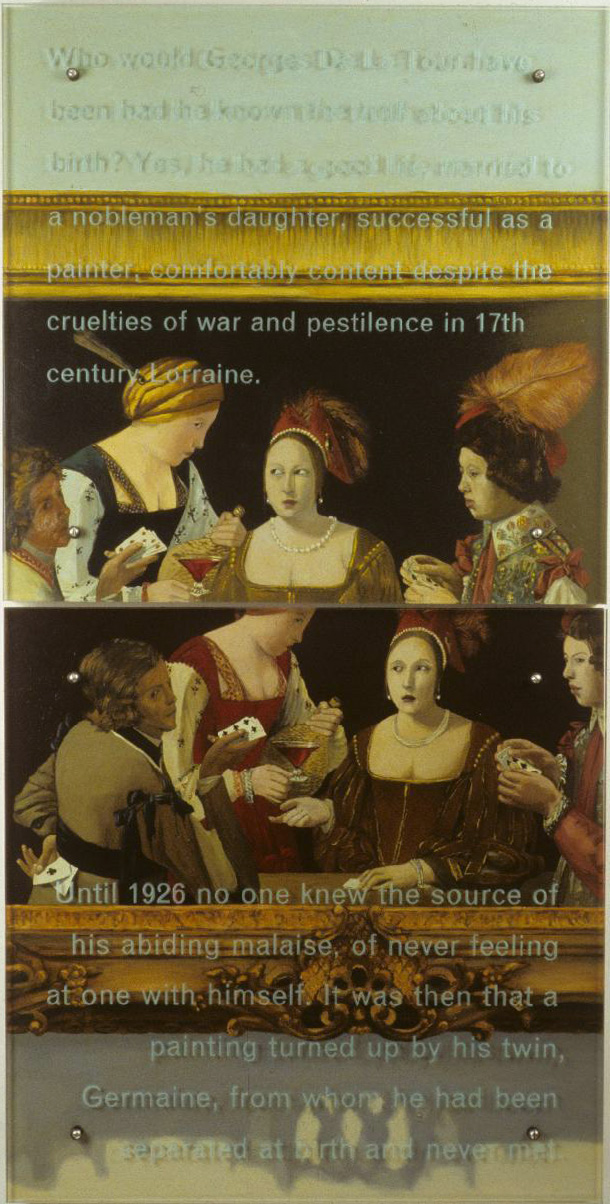

After Georges De La Tour, The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds, c. 1625

Georges De La Tour, The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs, c. 1625

TEXT:

Who would Georges De La Tour have been had he known the truth about his birth? Yes, he had a good life, married to a nobleman’s daughter, successful as a painter, comfortably content despite the cruelties of war and pestilence in 17th century Lorraine.

Until 1926 no one knew the source of his abiding malaise, of never feeling at one with himself. It was then that a painting turned up by his twin, Germaine, from whom he had been separated at birth and never met.

NOTE: Georges De La Tour, born in Luneville, Lorraine (now France), in 1593, died in 1652 of Spanish influenza. He left no letters, and consequently very little is known about him. He married a nobleman’s daughter, Diane Le Cerf, who probably is a face that appears in many of his paintings; the marriage was reported to be a union of great love. Diane died of the same epidemic as Georges on January 15, 1652; Georges succumbed to the disease fifteen days later.

Apparently he made two versions of the painting of the card cheat, a statement about the perils of wine, women and drink, but also one that warns of the evils of cheating (or in other words, lying).

Until recently (1972, when it was publicly exhibited as a De La Tour at the Orangerie in Paris), The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs was considered by many to be a fake. It carries no signature.

The Louvre Cheat was discovered in fact in 1926, and was bought by the Louvre in 1972. The Kimbell Cheat had been in a private collection in Geneva since at least the end of the 19th century. It was acquired by the Kimbell in 1981.

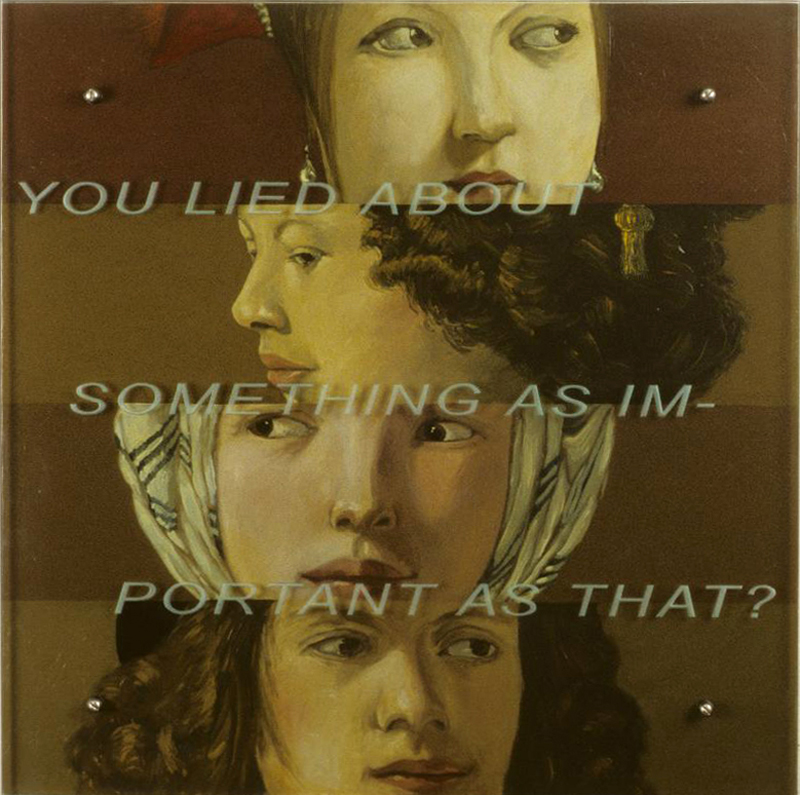

TEXT: You lied about something as important as that?

After (all) Georges De La Tour, The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds, c. 1625, Louvre, Paris

The Fortune Teller, c. 1625, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York